The Gilded Age era of New York grew brighter than ever on the day the Brooklyn Bridge was completed in 1883. Dubbed “the Eighth Wonder of the World,” the bridge took 14 years to complete and is now synonymous with New York City’s iconic skyline. But beneath the wrought iron and the waters of the East River lies a rarely-told, sinister truth about the bridge. A total of $15 million was spent to build the Brooklyn Bridge, but the countless lives lost in the process proved to be a much greater cost.

A precarious undertaking

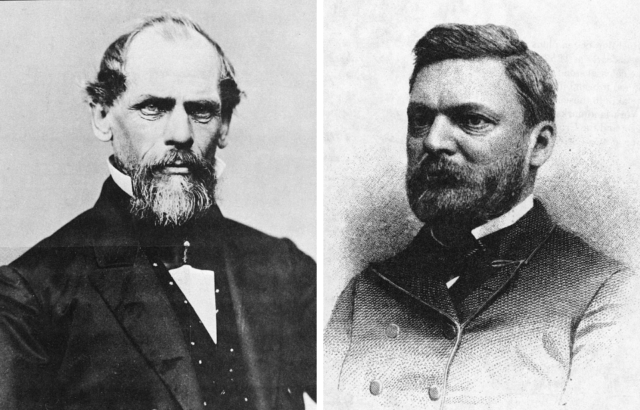

Building a suspension bridge is no easy feat even by today’s standards, and we can only imagine the difficulty of undertaking a massive underwater construction project in the mid-19th century. The Brooklyn Bridge was designed by John A. Roebling, a German-American civil engineer who specialized in suspension bridges. Construction began in 1869 to create a suspension bridge spanning over 6,000 feet across and 135 feet down into the East River.

No one could have foreseen how long the project would take, or the sheer number of fatalities that occurred even before construction began. The man who designed the bridge was also its first victim. On June 28, 1869 – months before construction was even underway – Roebling was surveying the location of the bridge tower while on a ferry slip along the Brooklyn waterfront. His foot got caught on a rope and was crushed. After having two toes amputated, Roebling contracted tetanus and died, leaving his 32-year-old son Washington Roebling in charge of the bridge construction.

On October 23, 1871, the first construction fatalities occurred when a pair of derricks – tower-shaped lifting devices – used to haul stone blocks to the top of the bridge tower suddenly fell. A wooden boom cleaved off the top half of rigger John French’s head and crushed a man named Dougherty. Another worker named John McGarrity died while trying to jump to safety, and another stone worker, Thomas Douglas, later died from his injuries.

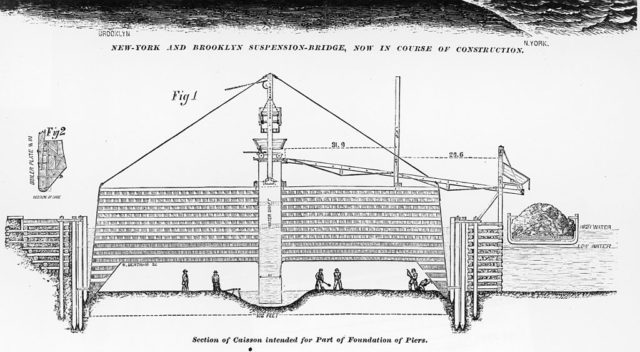

When the construction process moved underwater, workers continually surfaced dead or seriously ill and no one could explain why. The workers, known as sandhogs, were charged with excavating the riverbed while working inside watertight chambers made from wood and steel that had been sunken into the river to make room for the bridge tower foundations. Inside these chambers called caissons, sandhogs toiled in the unbearable heat inside metal boxes. The atmospheric pressure was doubled to what they were used to due to compressed air that was pumped into the chambers to keep water out and allow the workers to breathe.

‘The bends’

The deeper they dug, the more workers began to surface from the caissons showing strange symptoms including muscular paralysis, vomiting, sharp joint and stomach pain, chills, and slurred speech. The disease eventually became known as “caisson disease” – another term for decompression sickness of “the bends.” Decompression sickness was first documented in 1841 by French geologist Jacques Triger, who observed decompression symptoms in miners working in similar caissons. The sickness was named “the bends” because victims characteristically bent their backs.

By 1873, Dr. Andrew Smith presented his own report on the decompression sickness experienced by the Brooklyn Bridge workers. He recommended the implementation of chamber recompression to help reverse the effects of the bends before workers fully surfaced. What the sandhogs and miners were experiencing was the use of compressed air in the caissons that contained both oxygen and nitrogen. The nitrogen is dissolved in the bloodstream, and the deeper you go or the longer you stay submerged, the more nitrogen builds up in the body. If you surface too rapidly the change in water pressure causes tiny bubbles of nitrogen gas to form in the blood, which interrupts blood flow and damages blood vessels and nerves.

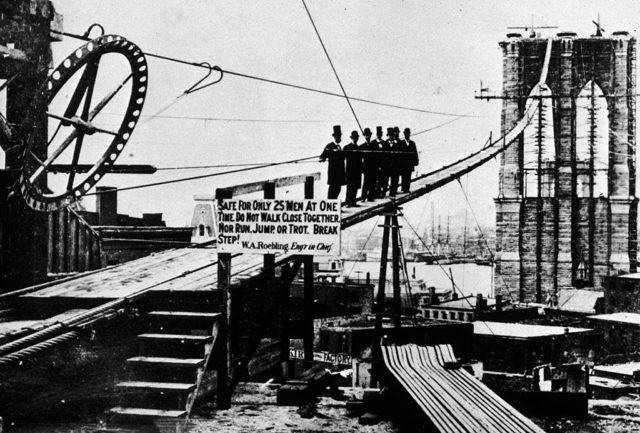

The first laborer to die from the bends while building the Brooklyn Bridge was John Myers, who collapsed at his home after only two days of work on the river. Eight days after Myer’s death, Patrick McKay died shortly after resurfacing and by the end of the month a third laborer, Daniel Reardon, also succumbed to decompression sickness. Washington Roebling halted the digging process soon after the deaths occurred and decided not to reach bedrock to avoid further fatalities. Roebling himself even experienced the horrors of the bends after spending countless hours monitoring the project in the caissons. He eventually became bedridden but didn’t stop supervising the construction, watching from his room using a telescope and relaying any feedback through his wife.

Even after the horrific caissons were condemned, tragedy continued to befall the Brooklyn Bridge. While building the 275-foot-tall bridge towers, several workers fell to their deaths while others were killed by massive falling stone bricks. In 1873 a German rigger named Peter Cope (also spelled Koop) became one of the most horrific casualties of the Brooklyn Bridge when his leg was caught in a rope that was wound around a hoisting engine, crushing his leg and killing him instantly.

By the time the bridge was completed, at least 24 men had died in the process.

Is the Brooklyn Bridge cursed?

Even after the bridge was completed, death continued to plague the landmark. It was officially unveiled on May 24, 1883, with a grand display of fireworks. Seven days later, a crowd of 15,000 to 20,000 New Yorkers gathered on the bridge on Memorial Day for a stroll down the promenade. The sheer number of people clogged the narrow staircase leading up to the bridge. When a woman slipped and fell down the stairs it triggered panic as people struggled to get away and pedestrians were packed in together. The panic was compounded by rumors that the bridge was going to collapse.

One eyewitness recalled the gruesome scene: “Within a few minutes there were piles of crushed and bleeding pieces of humanity at the foot of each flight of stairs and the panic-stricken crowd was trampling them to death.” Twelve people died during the stampede.

More from us: Why Lone Toilets Sit In the Middle of Pittsburgh Basements

All the accidental deaths that have happened in the early years of the bridge have left many wondering, is the Brooklyn Bridge cursed? No one knows if the fatal origins of the bridge were due to 19th-century construction techniques or a curse that befell the Roebling men. Washington Roebling refused to even set foot on the engineering marvel he helped to create, potentially because he understood what many overlooked: the bridge was also a monument to the countless men who lost their lives trying to build the “eighth wonder of the world.”