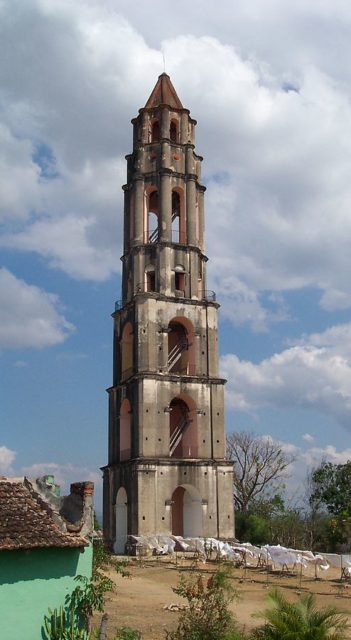

The Valley of Sugar Mills, or Valle de los Ingenios, is actually three connected valleys that serve the same purpose. They valleys were home to a great number of sugar mills and were the main sugar producer for all of Cuba from the late 18th to the end of the 19th century.

The workforce consisted of more than 30,000 slaves. The names of the three valleys are San Luis, Santa Rosa, and Meyer. Together they cover around 105 square miles (270 square km).

The industry of sugar production was incredibly important for Cuba. Introduced by the earliest Spanish settlements in 1512, by the 1700s, the island of Cuba was the world’s most prominent sugar producer. Conditions were perfect: ideal climate and soil, fresh water from several rivers, many good ports for export and plentiful connections on the island itself. A railway line was also laid to connect the Valle de los Ingenios with Trinidad and the nearby port of Casilda.

The native Cubans were made virtually extinct by diseases brought from Europe and poor treatment as slaves, and as a result, the Spanish started to bring over Africans to work as slaves in the fields and mills. Even though the Spanish abolished slavery in 1820, the practice of using African slaves in Cuba remained until the Wars of Independence in the 19th century. This marked the end of the Valley of Sugar Mills. Once the slaves had been freed most of the mills were shut down and abandoned, and soon fell into disrepair.

There are more than 60 archaeological sites in the valley. Of the original 18th century buildings, 13 big haciendas remain. Some are in very good shape with their original boilers and systems: remnants of what was once pioneering technology in the industry of sugar refinery.

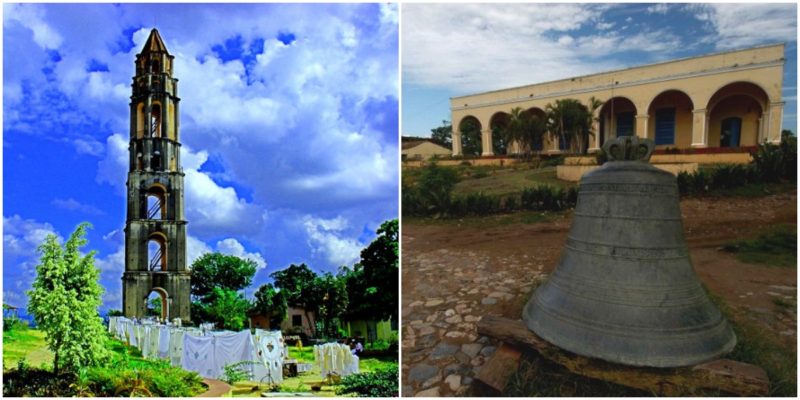

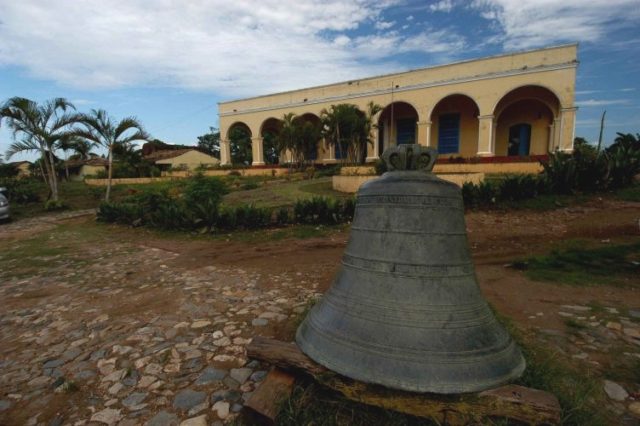

The most famous building in the valley is the Manaca Iznaga Tower. It stands at 147 ft (45 m) and was constructed in 1816 by the owner of the richest farm in the valley, Alejo Maria Iznaga y Borrell. According to locals, the amazing view over the valley is worth the 136-step climb to the top.

The tower was built to convey a sense of power for Iznaga: both over his slaves and the sugar industry as a whole. At one time it held the title of the tallest structure in Cuba. It also served another purpose. At the top of the tower was a bell that announced the beginning and the end of the working day for the slaves.

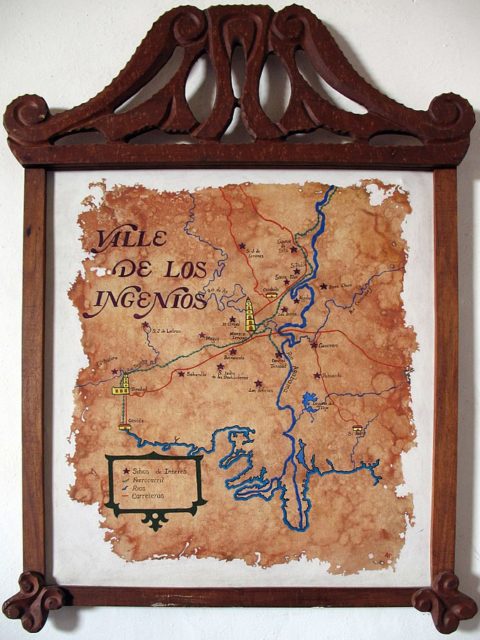

It also rang three more times every day to signal the time for prayer: the only relief the slaves would have from their work. It also served as a watchtower, surveying the fields for any slaves who dared to attempt escape. Today the bell lies next to the tower at the bottom. A symbol of the passing of time, and of actions which thankfully have no place in today’s society.

The Cuban Office of Conservation was given the task of restoring the abandoned sugar mills. The project began in 2000 and still continues today. Casa Guámairo was among the first of the damaged buildings to be restored. It served as the master’s house and had a lavish interior, adorned with murals by the famous painter and architect Daniel Dall Aglio in 1859. This villa was included alongside the San Isidro de los Destiladeros Mill and a few other buildings in the UNESCO world heritage list in 1999.