There is a joke about the Eglinton ghost. A young American woman goes on a tour of Eglinton Castle and the croquet lawns. The female tour guide asks how she liked the tour. She said that she had been a bit worried about seeing the Eglinton ghost in a dark room.

The guide said, “Don’t worry. I have not seen a ghost the whole time I’ve been here.”

She asked “How long has that been?”

The guide replied “About 220 years.”

~ William Roy Grandey, Murder, Mystery and Croquet: Wicket People Wield Murderous Mallets – True Stories.

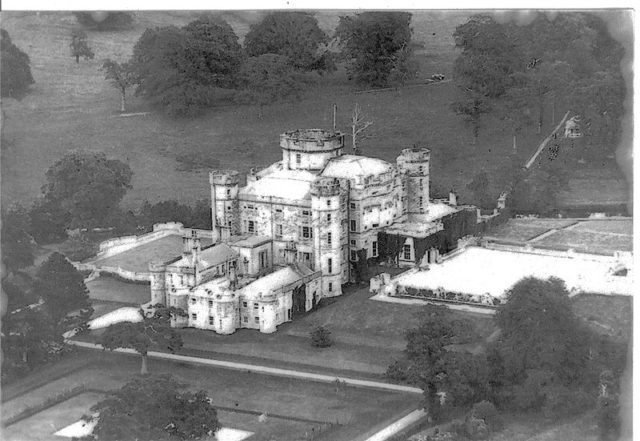

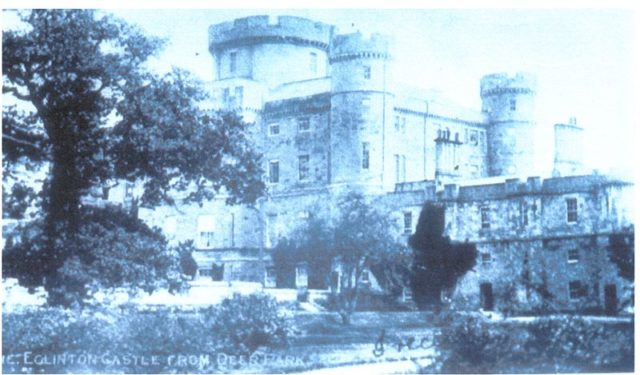

Today, it is a quiet scene. Sandstone leftovers of a once grand Gothic mansion stand serenely on a grassy hillock in the middle of Eglinton Country Park, North Ayrshire, Scotland. As the ancient seat of the Earls of Eglinton, the estate has seen the rise and fall of this family of Scottish nobles.

Eglinton Castle is perhaps most famous for three things: first is a unique form of “extreme croquet” that scandalized polite society of the mid-1800s. Then we have the ghost of a woman, whose skeleton was allegedly found inside the wall of a room that had been locked for as long as anyone could remember.

Local urban legend tells that she haunts the site of the former croquet field, hunting for a lost ball.

Could these two pieces of trivia be related? We will never know.

Finally, the thing for which the name of Eglinton is most remembered — the lavish, Medieval-revival Eglinton Tournament of 1839; a sodden victim of the unpredictable Scottish weather. It was a hugely extravagant and well documented affair.

And, of course, the old castle is said to have had a secret tunnel. The passageway allegedly runs from the Montgomerie family burial vault underneath Kilwinning Abbey — roughly 20 miles away, as the crow flies.

The story of the mystery skeleton starts at Eglinton Castle’s end. By the 1920s, things weren’t going so well financially for the Montgomeries. They had invested a large amount of money to build a harbor at the nearby town of Ardrossan.

When a large inheritance tax was added on top of the high costs of maintaining a building of such immense size, the family decided to cut their losses and leave the castle.

What followed next was a vast sale of the castle’s furniture and artworks that took place in December 1925.

An auction of the “Catalogue of the Superior Furnishings, French Furniture, etc.” was held by Edinburgh-based Dowell’s Ltd. on “Tuesday, 1st December 1925, and four following days,” according to the Eglinton Country Park archive. Almost 2,000 individual pieces of family history were sold off, including an account of the Tournament.

Anything of value was salvaged from the property, including the wood paneling. Ghost-hunters will whisper that there was a room that had not been unlocked since the castle was still shiny and new, during the days of the 12th Earl of Eglinton.

It had certainly been unused for a very long time. On removing one particular wooden wall panel, the lone workman made a gruesome discovery.

Right there, walled in, was the skeleton of a long-dead adult female. For whatever reasons, perhaps the landowners just didn’t want a fuss, the incident was never reported to the police. Instead, apparently someone knew a medical student who came and discreetly removed it. Did you ever wonder where the skeleton in your high school science class came from….?

The castle stood empty, and in 1926 its roof was removed to avoid paying roof-tax. Open to the elements, its fate was now sealed.

However, this was not the first Eglinton Castle. Built possibly in the 13th century, the original castle was burned down in 1528 by a rival clan.

It was rebuilt and stood for another 250 years before finally being demolished in the late 1700s. The “new” castellated country manor was erected by the 12th Earl of Eglinton between 1797 and 1802. The extensive grounds were landscaped and the gardens well manicured.

Life at Eglinton Castle became much more lively in the days of Archibald Montgomerie, 13th Earl of Eglinton, 1st Earl of Winton. He had an active political career, and was also Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. Lord Montgomerie loved golf, horse racing, and croquet.

Bored with playing by standard rules, the flamboyant Earl wrote his own. Among the oddities of this game was the addition of bells to each wicket and the scoring changed when they rang.

For reasons unknown, he named it “Captain Moreton’s Eglinton Castle Croquet.” According to Grandey’s book, “A surviving croquet set with the Earl’s original tunnels and wickets is still brought out annually for a tournament in West Scotland.”

But it was the 13th Earl’s medieval-style tournament in 1839 that really rattled people’s cages. Britain was in such a poor economic state that the coronation of Queen Victoria the previous year was so miserly as to be dubbed the “Penny Coronation.”

Lord Montgomerie, however, was not one to count the pennies. He envisioned reviving an idyllic notion of the age of chivalry, complete with knights in shining armor jousting on feisty steeds. There would be feasting and revelry on the lawns.

Invites for the three-day-long event went out to the Earl’s favorite the nobility and gentry of the day. Everybody who thought they were somebody made sure to show their face, and those who were taking part in the tournament itself practiced for a full year.

The Earl expected maybe 2,000 guests, but five times that many were asking for a ticket. He discriminated on grounds of their political beliefs: Only staunch Conservatives made the cut. It wasn’t enough though as he hadn’t bargained for up to 100,000 common folk travelling hundreds of miles to watch the spectacle.

The Victoria and Albert (V&A) Museum tells us that,“the Earl and his guests dressed themselves in medieval-style costumes and took part in processions and competitions.” In the end, though, the Eglinton Tournament was a total washout.

Imagine a boggy field, the specially made dress-armor of the “knights” dulled by torrential rain, their attendants and horses getting covered in mud.

As the V&A comments, alongside an oil painting that depicts Lord Eglinton and Winton, dressed as Lord of the Tournament under a clear blue sky, “Unfortunately it rained heavily and continuously on the Knights and Peers of the Realm in full armour with fully dressed horses.”

The weather, the bedlam of not having arranged enough places for people to stay, the fact that the Earl had gotten his contestants a free ride on the brand new rail line from Ayr to nearby Irvine, the blatant display of wealth when so many people were struggling to make ends meet, all of this mounted up. The 13th Earl of Eglinton was mercilessly ridiculed.

He is rumored to have been much more careful with his purse strings after those three wet September days.

After its abandonment, the castle went through its worst period during World War Two when it was used for target practice; the estate also became a military training ground for a short period. Most of what remained of the building was demolished in 1973.

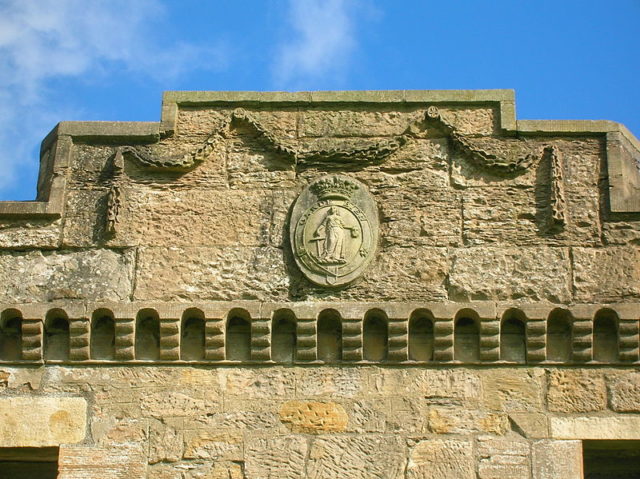

Visitors to Eglinton County Park can today see the ruins of Eglinton Castle — just a small part of the façade of one wing, some of the foundations, and a single lonely tower.