Not much remains of this convent in Paris, but its story is vivid enough to allow one to easily visualize its rise and fall. Towards the end of the 16th century a number of religious structures, all set up by supporters of the Catholic Reformation, were erected close to the main entry point of Paris, Porte Saint-Honoré.

More often then not, these religious complexes were set up by royal initiative. An example of this is the Order of Friars Minor Capuchin, which was set up in the imperial Tuileries Palace by the daughter of Lorenzo II de’ Medici, Catherine de’ Medici.

Henry III decided to purchase hôtel des Carneaux in 1585, with the intention to convert the place into a convent to house sixty members of the Feuillant order from Toulouse. The land bordered that of a Capuchin friary.

Two years later on July 11th, members of the order arrived in Paris. On September 8th, 1587, they were installed in the new convent. The convent was designed by Jean Baptiste Androuet du Cerceau, the designer of Pont Neuf, which is the oldest standing bridge on the River Seine in Paris.

Over the years, many monks came and went. The abbot, Jean de la Barrière, remained a close friend to Henry III and even preached at his funeral in Bordeaux.

Sadly, a great number of monks decided to leave during the French Wars of Religion, and at its end, the convent had no more than nine monks left. It managed to survive with the help of royal patronage, which it continued to receive after the end of the war.

After Henry III came Henry IV, and the new king of France made sure that the convent would survive the turbulence of the day. He granted it with the privileges of a royal foundation on June 20, 1597, and in August, Henry IV enlarged its lands by adding a new house. The property was acquired from Marshal of France Albert de Gondi.

During the reign of Henry IV, the convent church was completed. It was dedicated to a French abbot who was a major leader in the reform of Benedictine Monasticism, Bernard of Clairvaux. The church also received a large facade, financed by Louis XIII.

The French Revolution marked a huge turning point in French religion. Two decrees, one on May 13th and the other on July 16th, 1790, nationalized all church land, belongings, and buildings. Thus, Couvent des Feuillants became the property of the nation.

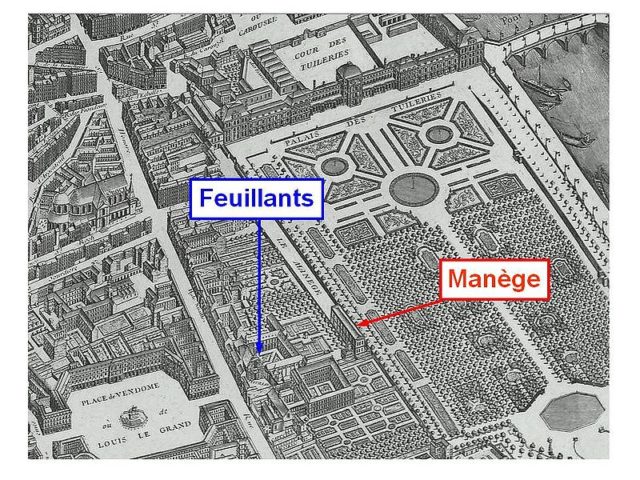

As a result, a great number of monks abandoned the convent. The property wasn’t sold for profit as it stood close to Salle du Manège, an indoor riding academy, which was a site of many deliberations during the Revolution.

A short time later, the convent’s complex was opened to the public and welcomed all sorts of merchants and artisans, including coffee and lemonade sellers.

The Church of Bernard of Clairvaux was also used for non-religious purposes. Jacques-Louis David, famous French painter and follower of the Neoclassical style, used the church’s nave to paint his famous The Tennis Court Oath.

The convent was used for purposes very far from its initial intention in the autumn of 1793, when its buildings were converted as a factory for arms manufacturing. The same year, an artillery museum was also opened on the site, remaining there until 1796 when it was transferred to Couvent des Jacobins.

The end for the convent came during the French Consulate. Much of the complex was demolished and thus lost, except for the guesthouses and the nave of the church. Today, the guesthouses stand at 229–235 rue Saint-Honoré in Paris.