Within the waters of Moreton Bay, Australia, stands an island named St. Helena. Although that name was given to it in the 19th century, its rich history goes back thousands of years. The native Quandamooka people were once the only inhabitants of the island; it was their fishing and hunting area, and a bountiful one at that.

Matthew Flinders found the island

From dugongs to flying-foxes, the island was incredibly biodiverse. For thousands of years, the Quandamooka people lived undisturbed until Matthew Flinders noticed the island in 1799. He was the first European to do so, and his visit changed the fate of the place forever.

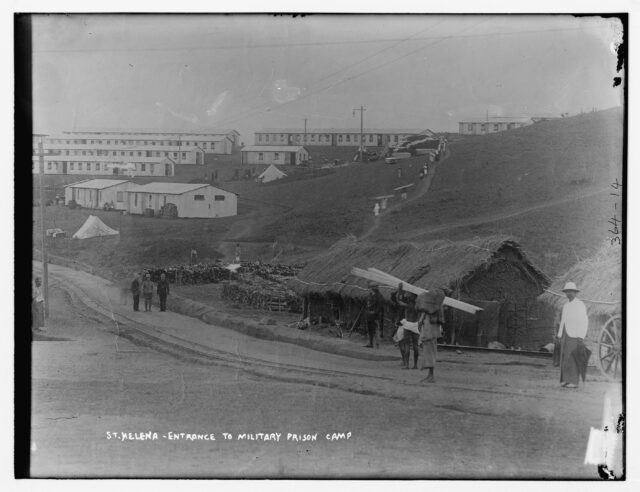

St. Helena becomes a prison

It took a while before the idea of converting the island into a prison was born. The idea was put forward in 1867, and the island received its new purpose. From 1866, prison labor was used to construct a quarantine station. Just one year later, the Australian authorities were forced to change their plans as conditions at the prison hulk called “Proserpine” got worse. The prisoners got a new order: construct a new prison on St. Helena.

Sugar milling at the prison

The new prison was completed one year later. Prison labor was used for everything. Two years after the prison was opened, a sugar mill was constructed together with sugar cane fields. The prisoners were to process the sugar – a task that kept them constantly engaged.

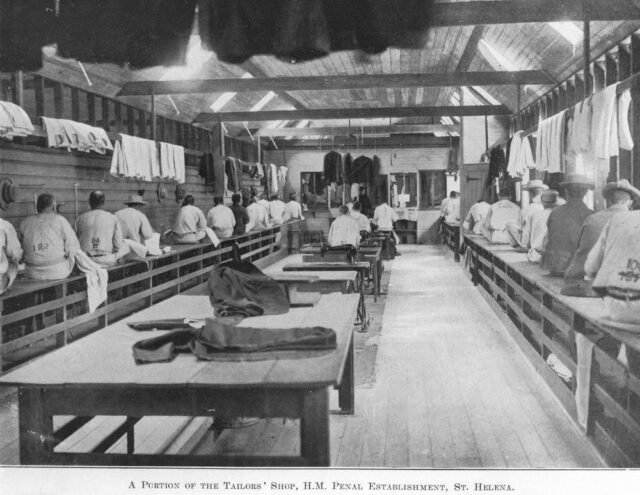

More work for the prisoners

This wasn’t the only work required of the prisoners. They were also responsible for producing sails, candles, and saddles, alongside carpentry work and boot making. The warders trained the prisoners and gave them their crafts. The warders were honored and were offered a place to stay on the island that was equal to their status.

Some of the prisoners became gardeners. Some had mastered this craft to a high level and went on to create one of the greatest gardens in all of Queensland at the house of the superintendent. Life inside the prison was defined by the constant workload.

Treatment of the prisoners

There were a number of ways of punishing the inmates such as lashing and food reduction after a hard day’s work. The reason the prisoners worked so hard all day was that the prison’s concept was to be a self-sufficient complex. For this, it needed its own land that spread across 50 acres.

The prison had a reputation for being escape-proof. A great number of prisoners tried their luck to leave the island but failed to do so; they were either recaptured or died in their attempts. Only one ever managed to escape.

Abandoning St. Helena

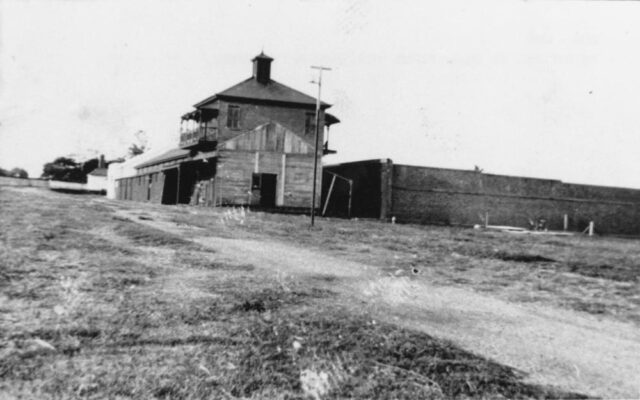

As years passed, the prison began to succumb to its age. During the 1920s, it was closed and the prisoners were relocated to Boggo Road Gaol. From that point on, it received another purpose as the farming fields still functioned. It was closed for good in 1932, although the demolition of some of the structures began in 1925.

Needless to say, even the demolition of the prison was done using prisoners as the workforce. The materials were taken to the mainland to be reused. The fate of the island remained uncertain for years until 1979, when it was declared a national park.

Today, the island attracts a great number of tourists and visitors who are eager to learn more and to experience firsthand what it was like to be on an island that offered no successful escape route. What was left of the prison and its ruins were conserved and still stand today: a reminder of the 19th century penal system.