In order to find out who St. Michan was, we have to go back to the fifth century. It is believed that St. Michan was the eldest son of the Welsh Prince of Brecknock who founded a cill (church) in Kilmacanoge in Ireland.

His Irish name is St. MoChanog, but the church follows the Welsh version, pronounced My-Can. Further down in history we find the name of St. Michan appears in the “Calendar of Irish Saints” and his feast day is given as August 25.

Upon returning from Dublin to his home in Wales in 496, he was killed. Today on Church Street in Dublin there stands a church dedicated to him, on the exact spot where a Norse Chapel once stood.

St. Michan’s began as a Catholic cathedral, built in 1095. It remained the cathedral of St. Michan until 1121 when this mantle went to the nearby Christ Church. In 1540, now under Protestant governance, St. Michan’s was dedicated as a church of the Anglican Communion. The current church has stood since 1686 but the design as seen today dates back to a reconstruction in 1825 by William Robinson, an English architect. It is the only such structure that still stands on top of a Viking base.

Judging from the outside, the church may not appear as much, but the inside of the church is a completely different story. The story about the church organ is unique, for it is believed that the baroque composer George Frideric Handel used this instrument to compose his “Messiah” in 1724.

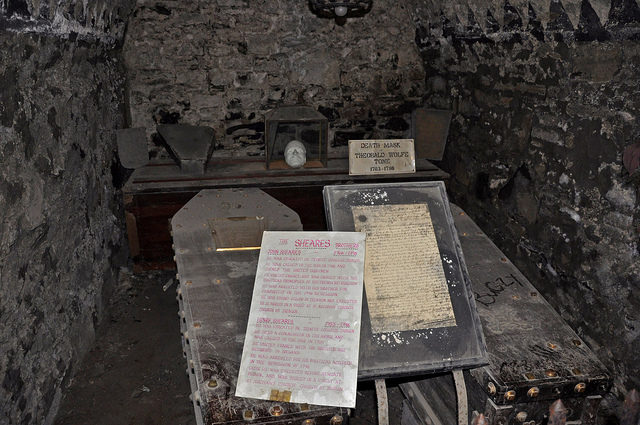

But this story is not about Handel nor the pipe organ. It is about what lies deep inside the bowels of St. Michan’s church. Descending a set of limestone steps takes you down in the vaults, a dark yet softly lit place that holds a number of mummies who both stubbornly refuse to decompose and to remain in their coffins.

The stories about why the bodies of these long deceased people became mummified are various. One claim is that the limestone from which these vaults are made keeps the atmosphere dry and it is just the right temperature and humidity to preserve the cadavers. Another theory suggests that it is due to the concentration of methane found in the air. Whatever the reason, the corpses remain well preserved, despite being long dead.

The four most well known of these mummies are a woman who is simply called The Unknown, for almost nothing is known about her life. Beside her lies The Thief who had both of his hands and feet chopped off, a common punishment for such crimes in those days. According to the scholars, no thief belongs in a crypt next to a Crusader. It is believed he might have changed his ways and became a priest, thus deserving an honorable place in the vaults.

Next to this supposed thief lies a woman. Given her small size, she was nicknamed The Nun. But the one mummy that lies separated from the rest and completely covered with dust, is the body of a man that died some 400 years ago. Dubbed The Crusader, this mummy has its legs crushed and neatly tucked underneath him for the coffin in which he was placed is much too short for his size of 6 and a half feet.

The story goes that this person was a soldier who lost his life on the battlefield. With time the coffin got rotten and revealed the long hands of this man. At one time, the visitors of this long forgotten crypt were allowed to hold his hand. Today no touching of the mummies is permitted.

There are a number of others whose bodies are brought and laid down here such as Irish lawyers the Shears brothers. There a total of 5 crypts down here, 2 of which are open to the general public.