While traditional rows of headstones in the local churchyard are certainly not going anywhere, in many areas, space is running short for new burial sites. Ideas to solve this issue range from creating Victorian-style garden cemeteries, which double as a public park, to Seattle’s Recompose project.

Okay, so we might not all feel comfortable at the thought of repurposing our body as compost. But gravesites are not always the eternal sacred places that we might assume.

So what about the graveyards of the past? Well, many have been relocated or even built over. (Queue Poltergeist music…)

There are some places that we go for a walk or buy groceries today where the ground underneath tells a different story. Hidden beneath are centuries of secrets and forgotten stories of people that once were. Here we present a small selection of defunct cemeteries that were used as recently as the 1800s.

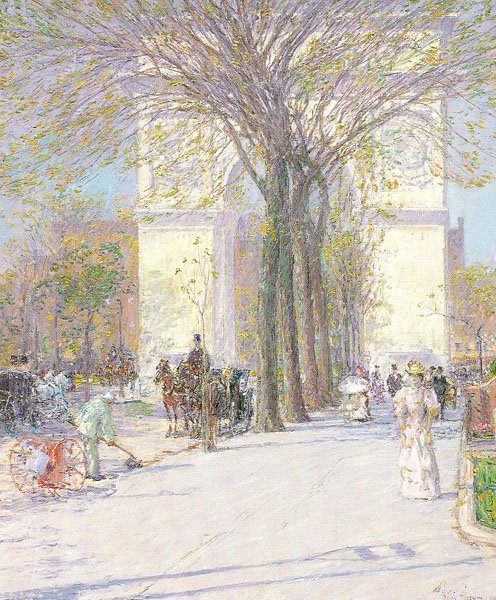

Washington Square Park, New York

What people of New York know today as a prime place for green markets and idle people-watching was once a paupers burial ground. Known to the indigenous Lenape tribe as marshland that was a prime spot for hunting wildfowl and trout fishing, the site that is now Washington Square Park was turned over as farmland in the mid-1600s.

Following the Revolutionary War the plot was assigned as a potter’s field — a burial ground for the city’s poor people, many of whom died of yellow fever. More than 20,000 people found their resting place there.

It took just 20 years to fill the potter’s field, after which the graves were buried and the square became an army drilling ground. It was formally dedicated as Washington Parade Ground in 1826.

While the dead rested in peace, troops were twice mustered in Washington Square to quell riots in the city; a labor riot in 1834 and the draft riots of 1863. After the Civil War, however, it was landscaped as a city park.

As a reminder of what lies beneath our feet, contractors working to replace the old water mains in November 2015 discovered two burial vaults. They have been respectfully left intact and undisturbed.

There is an urban legend about a blue mist believed to be the spirits of those laid to rest here, hovering above the park at night.

Lincoln Park, Chicago

This 1,208-acre park is now the place to go for a jog in Chicago. But in the past, from 1836 until the 1860s, it was only an inexpensive piece of land on the edge of the city. So, naturally, the cemetery was set there. Nearby was a smallpox hospital since the area was considered remote and somewhat of a natural quarantine.

While one section of the graveyard was used mostly for people who died from cholera, the site also had Catholic and Jewish quarters, as well as the main City Cemetery. Thousands of people were buried in mass pauper graves.

The city council voted in 1864 to relocate the graves and turn the site in a park. The Couch Mausoleum is today the only visible remnant of the old cemetery. However, a number of bodies were apparently “lost” during the transfer.

Over the years, works on sewage and water networks by the Chicago Park District have unearthed a number of skeletal remains. And in 1998, human bones dated as more than 100-years-old were found during construction of a parking lot for the Chicago Historical Society.

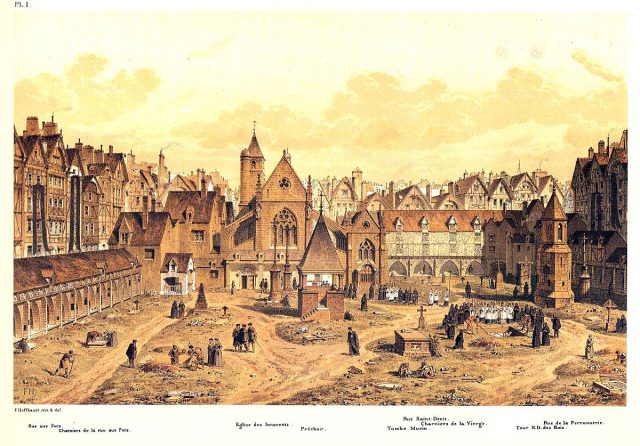

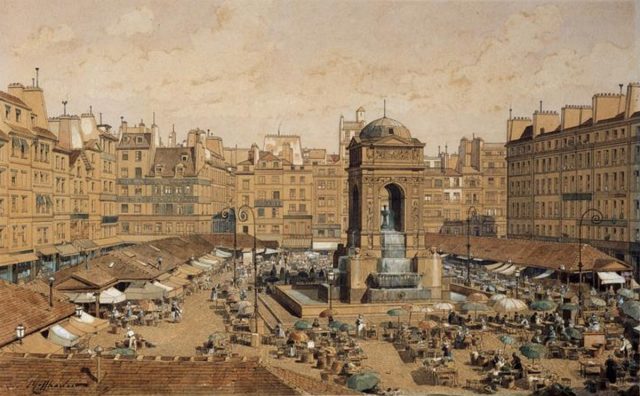

The Holy Innocents’ Cemetery, Paris

Le Cimetière des Saints-Innocents is the oldest cemetery in Paris. It was functional from at least the 12th century up until 1780, when it was closed after heavy rains caused part of a subterranean wall between a mass grave and the cellar of a neighboring house to collapse. Imagine waking up to find a cellar full of semi-decomposed corpses!

Complaints about the smell of decomposing bodies are recorded from the time of Louis XV (r. 1710-1744) but the place probably stank for a long time before that. The church charged handsomely for those who could afford a grand sepulcher, but the poor were also buried here. In large numbers. In mass graves — pits big enough to hold up to 1,500 bodies. They would be left in the open grave until it was full, then another one would be opened.

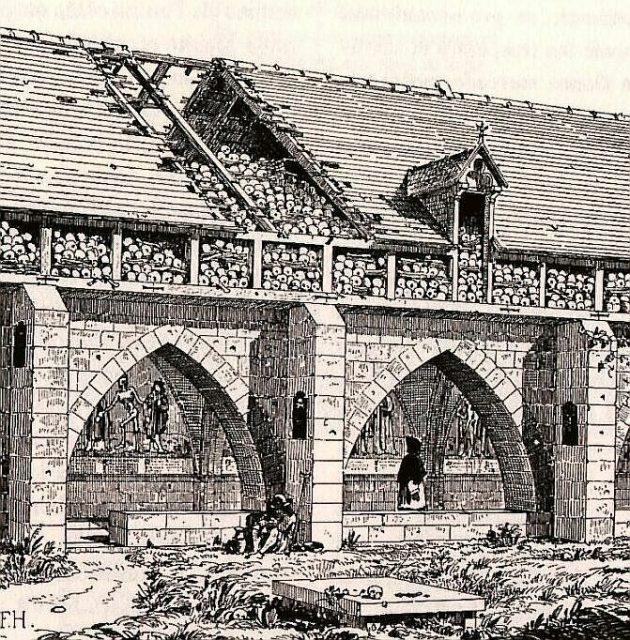

It was known for being so overcrowded that in the 14th and 15th centuries, charnel houses were built along the walls to hold the bones of old bodies that were exhumed to make space for the newly-dead to be put in the ground. The exhumed corpses were placed in the charnel roofs, allowing air to circulate from the arches below so the bones would dry out quickly.

For those that are familiar with the works of Anna Rice and The Vampire Chronicles, this place is very well known from the second book The Vampire Lestat. In Patrick Süskind’s novel Perfume the main character Jean-Batist Grenouille was born here on July 17, 1738.

As happened with a surprising number of old cemeteries, the bodies were exhumed in around 1786 and moved to an ossuary. This is a final resting place for storing the skeletal remains of people — for the corpses from the Holy Infants Cemetery, this was in a network of disused quarries on the outskirts of Paris.