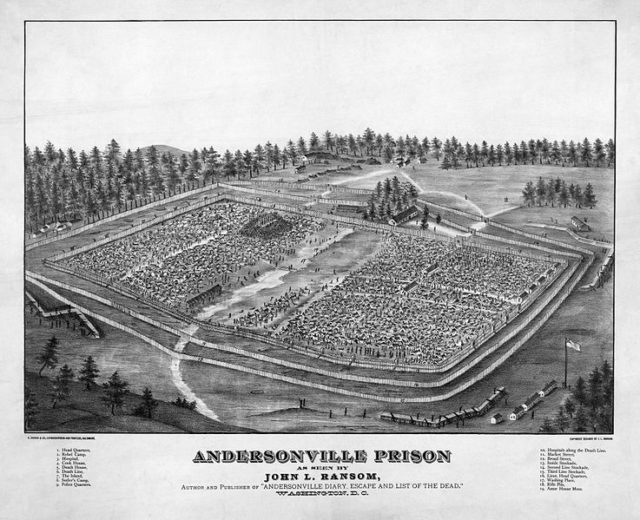

From the year 1864, there stood a prison located close to the edges of Andersonville in the southwest of Macon County in Georgia where captured Union soldiers were kept behind lock and key during the final year of the American Civil War. And a terrible place it was. People were cramped and confined in small areas, for this prison was overcrowded to three times its capacity.

Andersonville Prison

A parole exchange system had operated from 1861 to 1863, an agreement which allowed Confederate and Union prisoners of war to be exchanged, man for man. However, this broke down due to refusal by the Confederacy to recognize a black life as equal to a white one. The camps where these men had been held temporarily now became overwhelmed as neither side had made plans to house so many POWs long-term. To accommodate the prisoners, new camps were hastily set up.

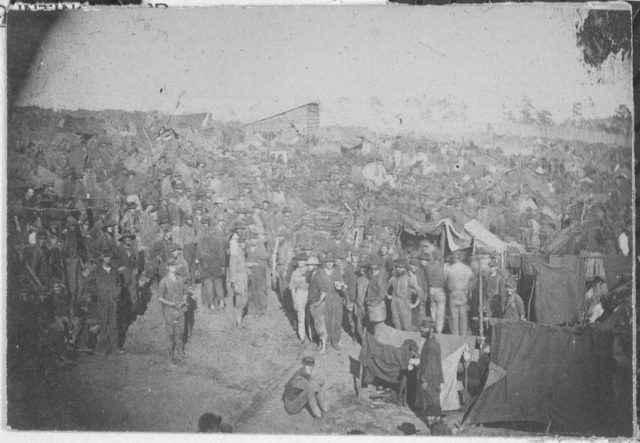

Conditions in Civil War prisons were, in general, unspeakably dire. Of the 409,000 soldiers held in POW camps, 56,000 died, accounting for 10 percent of deaths in the war overall. Andersonville Prison, officially known as Camp Sumter, was the final resting place for more than 1 in 4 of the 45,000 people held here. Sanitation was near-nonexistent. Drinking water was contaminated with faeces, and dysentery was rife among the population, already weak from lack of food and water. Death here was often slow and painful as diseases such as scurvy ravaged those unfortunate souls.

What went on within the prison walls

Once there, the newly arrived prisoners instantly became aware of what was really going on behind the 16 feet high paling. “…Before us were forms that had once been active and erect;—stalwart men, now nothing but mere walking skeletons, covered with filth and vermin; …and excrement covered the ground, the scent arising from which was suffocating” wrote Robert H. Kellogg in his book Life and Death in Rebel Prisons. He was a youngster, a 20-year-old Sergeant Major when this happened. And this is just one of numerous testimonies of the squalor in this place.

When it was first opened in February 1864, the rectangular stockade of Andersonville Prison enclosed 16.5 acres. The site was enlarged after just five months to 26.5 acres. To further discourage attempts to escape, an inner fence was erected. Anybody who put a toe across this flimsy railing, called the “Dead Line,” would be immediately shot with no warning. 351 prisoners did manage to break out, but most were recaptured. The only other way out was to be buried in one of the mass graves.

Trying to survive the camp

The Confederate army themselves were short on supplies, so new clothing for the prisoners was completely off the list. Their garments soon became worn from living in the dirt under sparse tents, so taking clothes from the dead was commonplace, and even a commodity to fight for. According to an account in The Civil War: A Visual History, “before one was fairly cold his clothes would be appropriated and divided, and I have seen many sharp fights between contesting claimants.”

Despite the attempts of President Abraham Lincoln to create rules that governed how POW camps functioned, Andersonville prison still pretty much followed its own rules which were based on–as Charles Darwin once put it–survival of the fittest.

The prison became a gang-run camp

The social network inside the prison came with its own set of rules. Prisoners with “friends” were more likely to survive than those who chose to remain alone. But hunger or thirst or sickness weren’t the only enemies the prisoners had to live with. Inside Andersonville, a gang was born that dubbed themselves “The Andersonville Raiders.” This ring of self-declared warriors was responsible for much of the thievery and black-market trading of food, water, and clothes. As a response, another group was created, called “The Regulators,” that sought to capture and prosecute all of the Raiders.

More from us: The Gulag-Style Incarceration of Political Prisoners at Spaç Prison

The chronicle of Andersonville ends in 1865 when the camp was liberated. Today this place is a National Historic Site that clearly depicts what really went on behind this wooden fence.