Built on top of a hill during the time when Avicenna was in its most fruitful years, William the Conqueror was born, and the Crusades were about to begin, this château has a rich history of its own and the bones of this millennium-old fort still survive today.

In its days of youth–in the 11th century–Château de Joux was a mere wooden structure that would not be built from stone until a century later when the nobility from Joux rebuilt the fort and dungeon. In front of it was a trade route, and the wooden building served as backup security for those collecting toll charges. It remained in this role for a good three hundred years.

A few hundred years later, Philip the Good, lover of fine art and patron of a number of excellent painters like Jan van Eyck and Gilles Binchois, bought this fort. Upon acquiring it, he altered this Château to a perimeter fort which meant that barracks and trenches were added. From that point on, the fort kept changing hands, beginning with Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy.

From Charles, it went to Mary of Burgundy, a Duchess, ruler of a number of territories, and the daughter of Charles the Bold. From Mary, the fort went to Maximilian I, the King of Romans – though he never went to Rome to be officially crowned for traveling such a distance in those days was extremely dangerous.

Next followed the Duchess of Savoy, Margaret of Austria, only to later end up in the Holy Roman Emperor’s Charles V’s hands. Every single one of them added some signature of their own to this fort. Finally, in 1678, the fort went to Louis XIV, the Sun King. Throughout the centuries the fort was altered but no alteration was as drastic as Vauban’s, who restructured the whole fort and gave it a modern appearance.

In 1814, the fort was seized by the Austrians. Some 65 years later, the military engineer Marshal Joffre further added to the overall structure of the fort and made it part of the Maginot line – a French tactic to fight off the Nazis during World War II. It was he who installed casemates that were designed to hold 155mm cannons, an astonishing piece of artillery for those days.

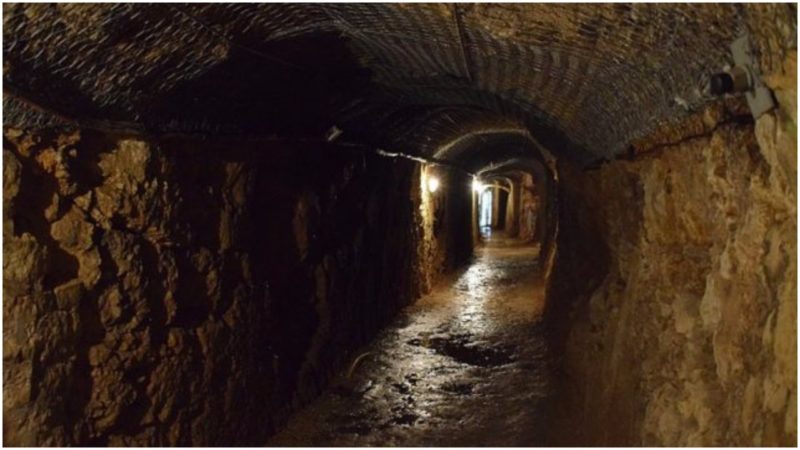

For three whole centuries, starting with the 17th and ending with the 19th, Château de Joux was also notorious for its use as a prison. In this role, the château became famous for this is where Toussaint Louverture, leader of the Haitian Revolution, was imprisoned.

During his military career, he changed sides a couple of times, at first fighting against the French and for the Spanish, then for the French and against the Spanish and then once more again France – though this time against Napoleon. He died in this prison on April 7, 1803.

The rest of the notable prisoners locked here include the Count of Mirabeau–participant in the French Revolution–and Heinrich von Kleist, a poet, short-story writer, and journalist.

Despite being a prison, this fort was largely used for defensive purposes, though never past 1958, when it stopped being a fort and became a tourist attraction.

Today this place serves as a museum, showcasing more than 600 weapons and other exhibits, all part of the fort’s 1,000-year history. For instance, a rifle that dates from 1717. This fort is also home to well that reaches an astonishing 147 meters and was once the deepest in the whole of France. It was also listed as a historic monument by the Ministry of Culture in 1949.