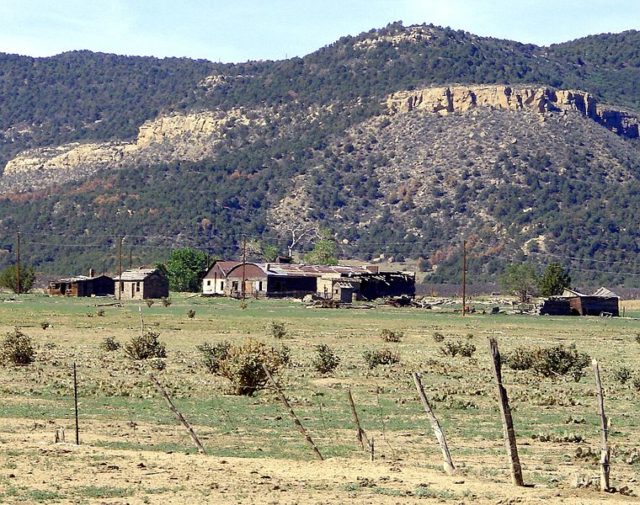

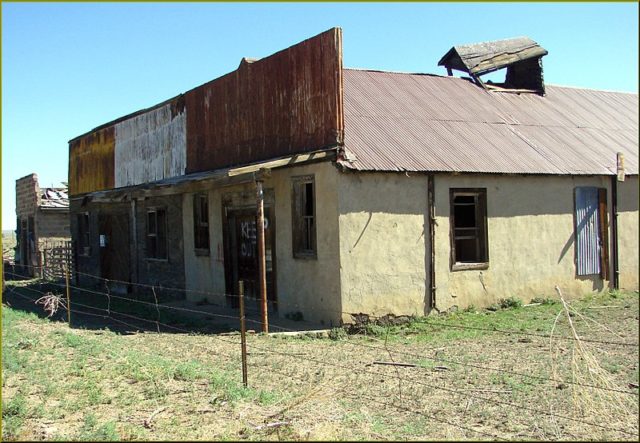

The town of Ludlow, or what remains of it, stands near the entrance to a canyon at the beginning of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. No more than 12 miles from the town of Trinidad, Ludlow rests in its melancholic solitude, affected for life by the ill-fated episode that took place on April 20, 1914.

On that day, the Colorado National Guard and guards from the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company opened fire upon a makeshift camp comprised of striking miners and their families, killing dozens of people.

To better understand the events of this particular day, we need to travel back one year prior to this date, when the Coal Field Strikes began.

Unified under the United Mine Workers of America, the miners compiled a list of demands that they found crucial (like a ten percent pay raise and shorter working days of eight hours) and forwarded it to The Colorado Fuel and Iron Company. Sadly, their demands were not met. Thousands upon thousands of workers began organizing themselves, many of whom were immigrants from as far as Greece and Serbia.

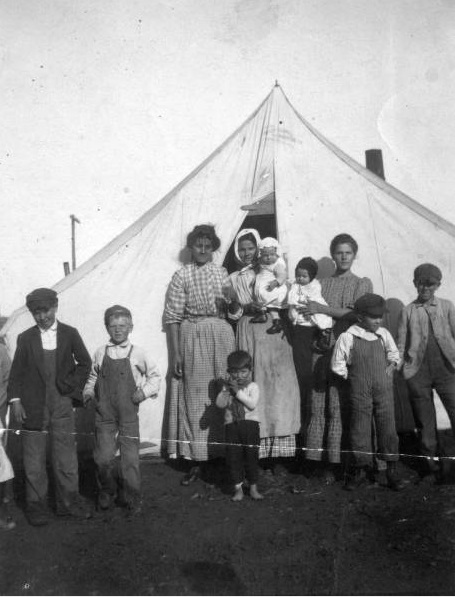

As a result, striking camps started to form in places such as Walsenburg and Trinidad. But by far the largest of them all was in Ludlow. The “rough and ready” settlement at Ludlow was comprised of no less than 200 tents and housed around 1,200 people.

Working in a mine is a hard and tedious toil, and the workers were at constant risk of roofs collapsing, explosions, and suffocation. For such hard labor, the miners were paid relatively low and at times were not given anything. They were paid by tonnage, and on days when no coal was extracted but other activities were undertaken such as reinforcing the walls of the mine, the workers received no financial compensation for their toil. The idea to pay the miners by tonnage was to attract poverty-stricken individuals and their families.

The equation was simple: the more coal there was to be extracted, the more money there was to be made. As the mines prioritized mining coal over making the site safe first, miners often lost their lives as a result of accidents. Hundreds of miners died, and hundreds of children were left without fathers in 1913 alone. Being paid for the so-called “dead work” was one of the demands on the list.

Day by day, the miners kept pushing on with their demands for better working conditions, and for the time being, the strike was relatively peaceful with only isolated incidents here and there. But then things veered off and took on a different turn. On March 10, 1914, a strikebreaker was found dead at a different camp in Forbes, Colorado.

As a result, an order was issued for the camp to be destroyed. The people at Forbes Camp suspected nothing and were saying their final goodbyes to two newborns that had died a couple of days earlier, according to some historical sources. The camp was completely destroyed.

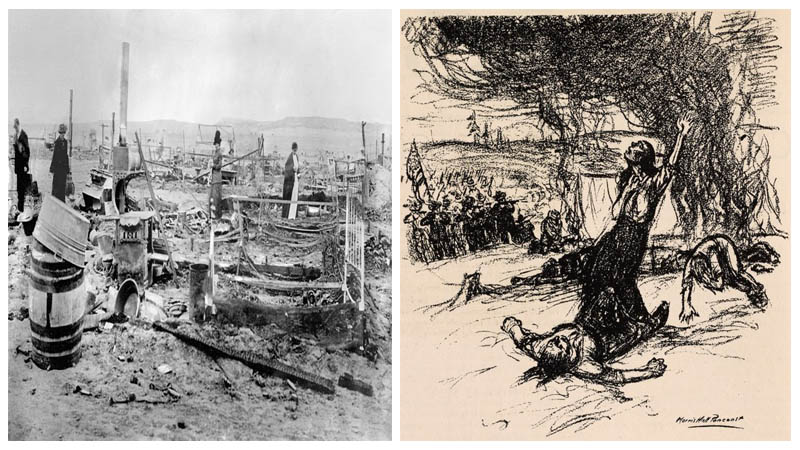

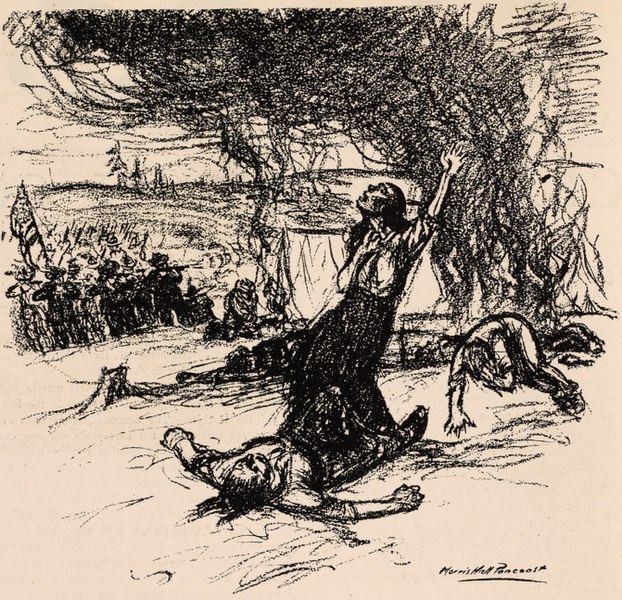

A month and ten days later, on April the 20th, National Guardsmen came to the camp. A machine gun was installed nearby, and the sound of two explosions of dynamite marked the beginning of the conflict. In no time, hundreds of people were under heavy fire.

Later that day, the camp was smashed and the people were scattered about. Twenty-one individuals were less lucky and lost their lives either by a bullet or suffocation; the youngest of them was just a several-month-old baby. The oldest victim was a man by the name of James Fyler, who was 43 when he was shot.

To this very day, the remains of Ludlow remain as scattered, ruined stone and rotting wood; but the “Ludlow Massacre” forever changed the industry for the better, as public outrage led to a report by the House Committee on Mines and Mining that was influential in altering legislation.