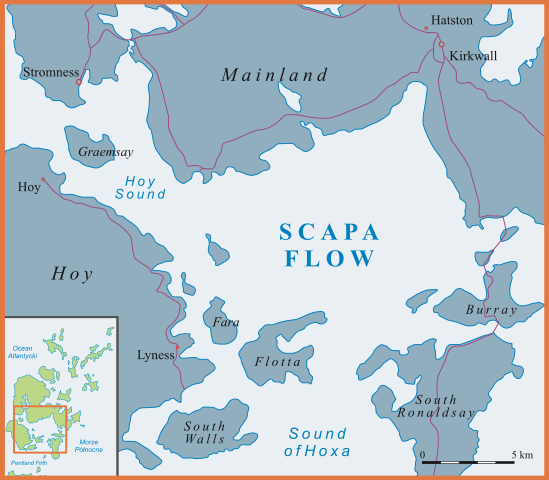

Two months after the start of World War II, war actions continued to increase while the German army succeeded on all the front lines. Slowly but surely, Germany took over Europe. However, thе highest German military commanders were aware that the German navy was lagging behind the British. A plan to attack the significant British Naval Base of Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands, north of the mainland of Scotland, was being made.

The Kriegsmarine submarine commander Karl Dönitz had planned a rather risky attack of Scapa Flow. He was aware of the dangers of such an action, regarding that two alike actions in World War I had been unsuccessful. The approach towards this perfect natural harbor was blocked by underwater mines, anti-submarine nets, and sunken blockships.

Submarines were at greater risk because the waters surrounding Scapa Flow had strong underwater streams that could reach speeds much higher than the speed of submarines at the time. Despite all the hazards, the Command of the German Navy decided to perform the attack and thus commenced with intensive preparations.

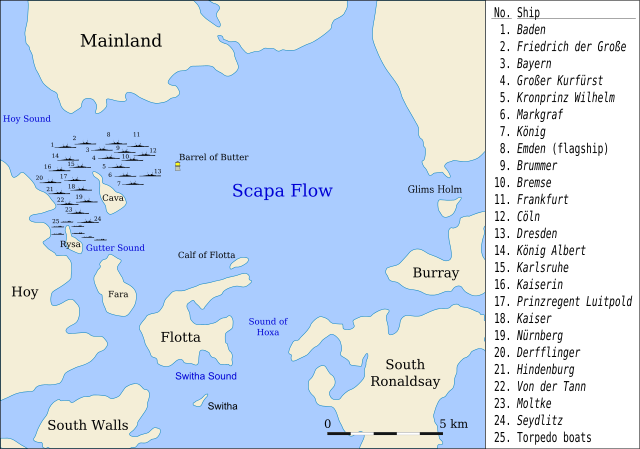

The aim of the Germans was to perform a small act of revenge. Following Germany’s defeat in World War I, 74 ships of the German High Seas Fleet had surrendered and arrived in Scapa Flow for internment. On June 21, 1919, after seven months of waiting and not knowing the details and the real outcome of the peace Treaty of Versailles, Admiral Ludwig von Reuter wanted to prevent giving the ships to the enemy and ordered the scuttling of the entire fleet. The British succeeded in saving some ships, but most of the fleet (52 ships) were sunk. In the 1920s, parts of the wrecks were raised out of the water.

But there was also another, more practical reason for the attack. The Germans thought that a successful attack on Scapa Flow would force the British Home Fleet out from their strategic base. They hoped that reducing the number of British warships in the area would loosen the British North Sea blockade and give Germany more freedom to attack the Atlantic convoys.

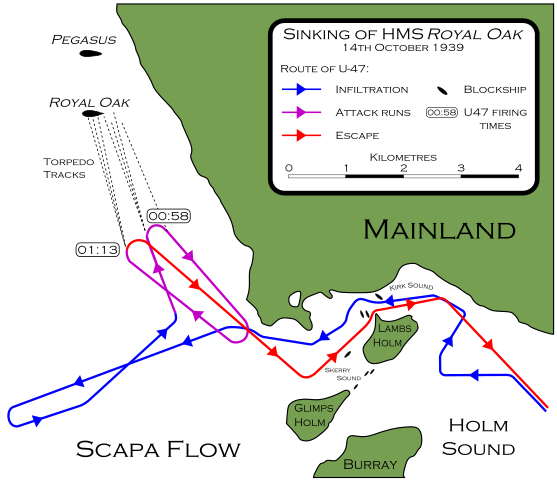

The Luftwaffe recorded the entire area at the end of September 1939, including Scapa Flow. The German submarine U-16 also participated in the process of data field collecting. After analyzing their data, they decided to enter from Scapa Flow’s east side through Kirk Sound. This was not a completely open entrance. It was defended by sunken blockships, but on the end of both sideways were narrow openings.

Admiral Dönitz still did not know that the main body of British naval ships had been transferred to Loch Eve, in north-west Scotland, to protect against any plausible attacks. The naval ship HMS Royal Oak was one of the few left in the old military base. Dönitz entrusted the mission to one of the most competent naval submarine commanders, Lieutenant Günther Prien, who took over the action without any second thoughts.

The night between October 13th and 14th was chosen as the most convenient moment for the attack. The night was moonless and the tide was expected to emerge twice. On October 8th, Prien left the port of Kiel with the submarine U-47, which weighed 750 tons. Four days later, he arrived on the east of the Orkney Islands and landed at the bottom of the sea.

The night of October 12th, U-47 headed towards the shore. The entire area was illuminated by the Aurora Borealis, so Prien could easily determine his position. He spent an extra day on the bottom of the sea. The following night, U-47 started its journey to the target. Getting through the narrow Kirk Sound, Prien had to use his great knowledge and experience when the submarine was trapped by the harsh streams. He arrived in Scapa Flow 30 minutes after midnight.

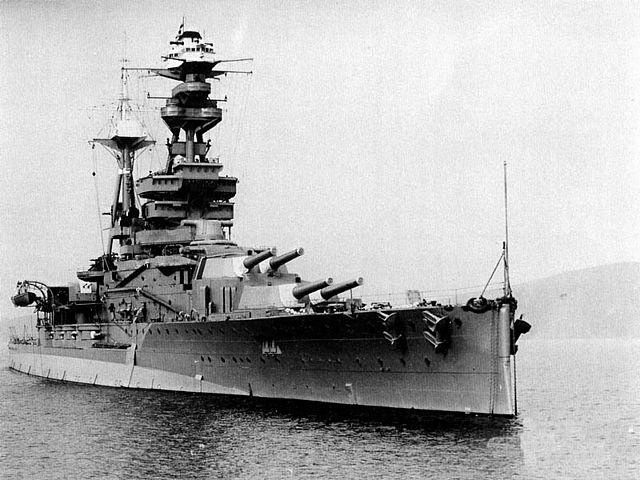

Prien noticed that the south side was completely empty. Several smaller Royal Navy warships and the Revenge-class battleship HMS Royal Oak, a veteran of World War I built in 1914, were anchored on the north. U-47 fired three torpedoes at a distance of approximately 3,300 yards. The last torpedo hit HMS Royal Oak. The British were unaware that the ship was under attack and thought that the detonation was some internal problem with the ship. But the next hit of three torpedoes set HMS Royal Oak into flames and thus hushed the silence on the cove.

Prien decided to return by the same route. He was confronted by the fierce water streams but still prevailed. Two hours later, U-47 sailed on the open sea. The action was successfully completed. On October 17th, U-47 returned to Germany. The British lost HMS Royal Oak and 830 men on the night of September 14th. They were startled by the attack. More than 1,200 people were onboard that fatal night. From German radio-reports, the British soon found out that the diversion was performed by the U-47.

Prien and the rest of the crew of the U-47 were welcomed as war heroes. Their reception in the Chancellery in Berlin filled the front pages of the newspapers. Prien’s courage and competence were later also recognized in the British Postwar Historiography. The original sample of the Fuehrungsbuch (Conduct Book) of Guenther Prien is kept at the Imperial War Museum. After the attack, the British reinforced the defense of their naval bases and ports, including Scapa Flow.

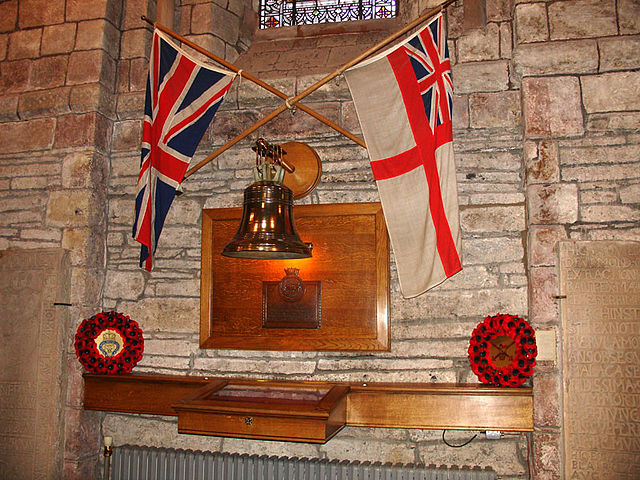

Scapa Flow had been used as a safe anchorage point since Viking times. The British Royal Navy used it actively until the middle of the 1950s. Today, the sheltered waters of Scapa Flow are a popular diving destination. While seven ships of the German High Seas Fleet, as well other wrecks and some of the sunken blockships, can be visited by civilian divers, unauthorized divings around the wreck of HMS Royal Oak are forbidden. The wreck is a designated war grave and can be visited only by divers of the British armed forces. There is an annual ceremonial event in memory of the crew, and that day divers replace a white ensign at the stern of the wreck. In the last decade, several operations to stop any significant oil leakage from the wreck were successfully carried out, but the situation is still monitored. The wreck is in good shape and silently sits on the sandy seabed. It holds with it a few important moments of history and the memory of the people that died that night during World War II.