Tucked away inside the cliffs of the Avon Gorge in Bristol, England, there lies a hidden gem of history. Cut through solid limestone rock is the 19th century Clifton Rocks Railway. This funicular railway once connected Clifton with Hotwells and Bristol Harbor, carrying passengers up and down an elevation of 240 feet. The construction of this railway was possible thanks to a financial help that came from the English publisher and editor Sir George Newnes, 1st Baronet, more commonly known as the “father of popular journalism.”

George Croydon Marks, 1st Baron Marks, was hired as the chief engineer responsible for the whole operation. This was the man responsible for other similar projects, including the Lynton-Lynmouth Cliff Railway on the other side of the Bristol Channel, in North Devon. The grand opening of the Clifton Rocks Railway took place on March 11, 1893.

It was a huge event that attracted more than 6,000 passengers on its first day, and more than 430,000 passengers used this railway the first year alone. The railway tunnel was 500 feet long. The highest point in its semi-elliptical form stood 18 feet from the ground with a width of 27 feet 6 inches, making it the widest tunnel of it’s kind at that time. The inside was almost entirely lined with bricks set in cement to add stability to the tunnel, in some places as thick as 2 feet.

The boring of this tunnel proved to be a challenge as the limestone, at certain portions so hard that constantly broke the drills of the workers, contained many faults. Drilling teams were set to work from both ends as well as from a number of shafts along the route. Steam powered drills using compressed air were used to drill through the rock, and steam power was also employed for pumping out surface water which constantly seeped into the workings.

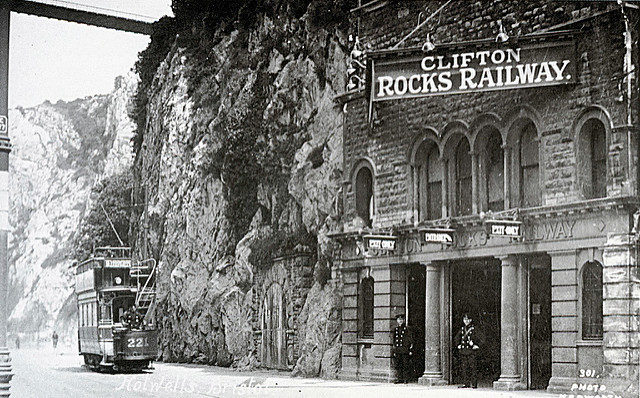

There were several rock falls both inside and outside the tunnel which caused delays in the construction. One which caused particular concern happened on January 31, 1893, less than two months before the railway was due to be opened. Around 20 tons of rock came down the rock face, almost hitting a horse-drawn tram and destroying part of a decorative wooden veranda at the tunnel entrance.

Needless to say, but being an underground inevitably required some form of light. The endings of the tunnel were naturally lit by the sun, but deeper inside they used gas lamps. The upper station at Sion Hill appears as a building no more than a story tall with a finely dressed facade of Bath stone that looks out across the Avon Gorge. Here, passengers and passers-by could watch the cars travel up and down through glass panels set into the pavement.

From day one, this railway functioned using no more than four cars which were similar in design to the horse-drawn tramcars that were popular during the 19th century. A pair of cars were coupled together on each of the two narrow gauge tracks so that one pair traveled up while the other came down. Steel cables connected the cars to a pulley at the top, but it was gravity that moved the cars using a water balance system. It worked a bit like a balance scale; the car at the top had water added to it’s ballast tanks which would make it heavier than the weight of the car that was to come up, then the water was dumped out at the bottom and pumped back to the top to be reused.

The passenger section of the cars had 18 seats and ended with a sliding door at each end. The brakesman rode on the platform at the bottom, river-facing end. Given the dark interior the tunnel, the cars were painted with a light shade of blue and white with gold trimming. They were repainted in different colors once they became part of the Bristol Tramway Company at a later date.

With declining passenger numbers and following a costly dispute with the City of Bristol over the ownership of a small section of land, the Clifton Rocks Railway Co. Ltd went into receivership. The Clifton Rocks Railway was acquired by the Bristol Tramway and Carriage Company Ltd. on November 29, 1912.

The railway was finally shut down on October 1, 1934. The tunnel saw some use during world war two by the British Overseas Airways Corporation who set their offices here and used part of the tunnels for storage. The BBC set up their secret back-up studio here in case Broadcasting House in London was bombed, though it thankfully was never used.

An interesting fact is that BBC had originally planned to use the nearby disused Bristol Port & Pier Railway tunnel as their emergency headquarters. However, in truly British style, the company sent a 100 member orchestra conducted by Sir Adrian Boult into the tunnel in order to test the acoustics before they would agree to set up there. During this delay, members of the public began using the port tunnel as an air raid shelter, so the BBC had to use the Clifton Rocks tunnel instead. Today the railway remains abandoned, though efforts are being made to preserve this place. The cost of doing so will reach an estimated sum of £15 million.