The history of the Ronchamp Coal Mines spans hundreds of years. They opened their first mine in 1810. The story of the Notre-Dame Mine Shaft, however, begins in 1851, about forty years later.

In the commune of Champagney northeastern France, in a hamlet called Éboule, is where one can find the Notre-Dame Mine pit. But the Ronchamp Mining Company is not the one that bored the first couple of meters in this pit. The initial digging of the first shaft was done by a French company known as la Société des maîtres de forges or “The Forge Masters.”

They began their work on December 14, 1851, on a piece of land no bigger than 130 square feet. Four years later, there were around 21 miners, 2 machinists, and 2 explosive experts that worked in this mine.

Then in 1856, the work was paused for a brief period, when the pit extended almost 900 feet below the ground, so that a survey could be conducted. The survey concluded that there was coal present at 1625 feet. The miners were able to reach this depth and go even deeper.

By 1859, they reached a depth of 1640 feet. Down there the miners ran into a coal vein with a thickness of about 2.5 feet. But these dimensions were way less than what the mining company considered a minimum requirement.

The working conditions at that time were far from humane and the miners were faced with harsh conditions; for instance, the ventilation of the mine was almost non-existent. This was the cause of a methane explosion that happened in 1861, in which three miners lost their lives.

After the explosion, work at the mine was understandably halted until a shaft could be dug for ventilation, which was achieved in 1861. Once finished, the shaft was approximately 6.5 feet wide. However, in 1862, two workers were tragically killed in a mysterious explosion. The miners were deprived of oxygen and suffocated.

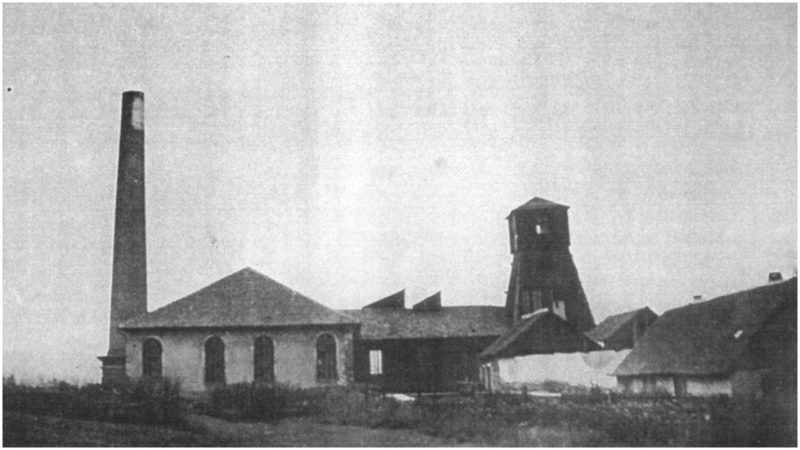

By the time Ronchamp became the owner of the mine, the conditions at this place were very poor. What remained of the buildings were in a desperate condition and the steam engine that was used to power the extraction elevator had two different gears, which caused a terrible shake and positional hazard.

One of the gears was 4 inches smaller than the other one. This difference caused the elevator to constantly break down and put the lives of the miners at risk. The headframe above the shaft was made of wood and in a state of despair and the shaft framework was crumbling.

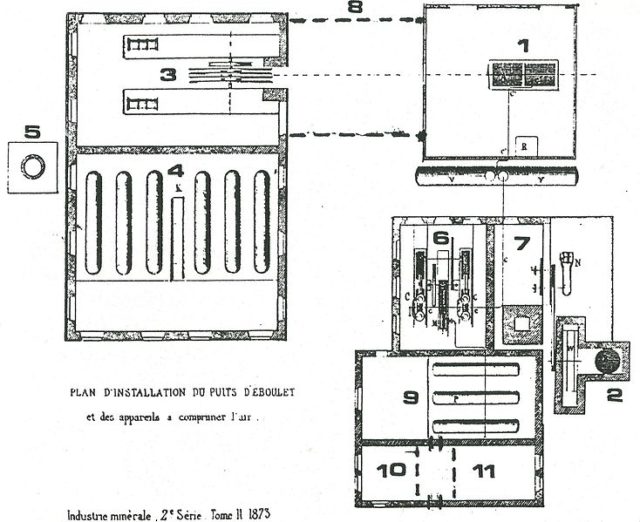

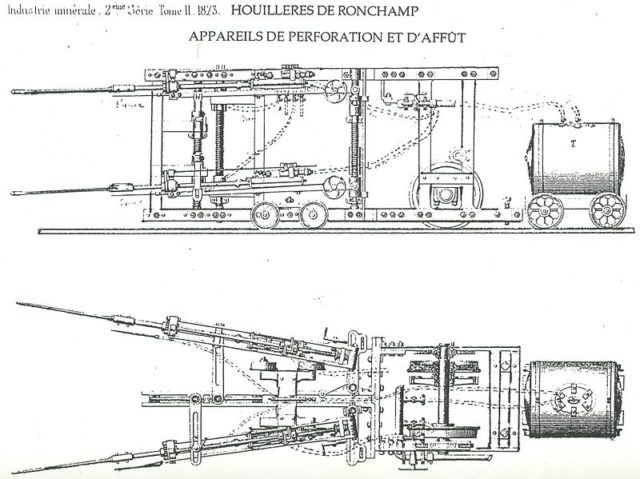

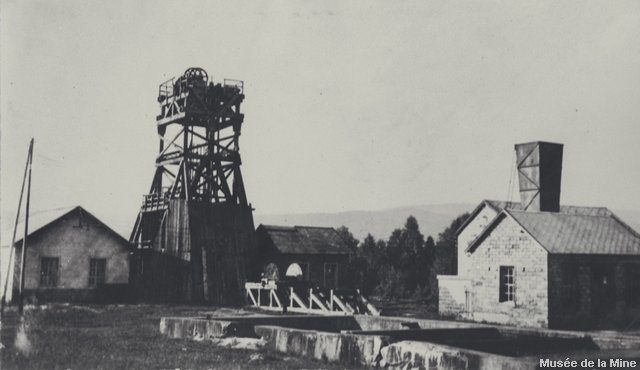

And so in 1967, the mine was overhauled. The old elevator was replaced with new 100 horse-power machines for extracting the miners. A new ventilator for the vent shaft was added, as well as an air compressor.

The miners were also provided with a lamp shop and a baths. One hundred new mine carts were purchased, each one capable of carrying at least 200 lbs more than the old carts.

It was Saint-Charles mine that received these old carts which replaced their even older wagons. The overall investment at this mine for its refurbishment was around 160,000 French francs. After this investment, the mine was ready to go back to excavating coal once again.

The mine continued with activities until it was officially closed four years before the turn of the century in 1896. After 52 years the mine was finally plugged.

Today there is a monument made by Bernard Poivey that stands right on top of the extraction shaft.