In the lowlands of Laxey on the Isle of Man stands Snaefell Mountain. On its sheer slopes there once stood a mine dubbed The Great Snaefell Mine, the history of which stretches across half a century and yet it is remembered for the tragedy that occurred there.

The history of mining in the Isle of Man and the search for precious metals began during the Bronze Age. Archaeologists have located this early mining sites around the Langness Peninsula and at the headland of this isle known as Bradda Head. Here, copper can easily be been seen on the surface and upon the face of these cliffs, which has attracted people for countless years.

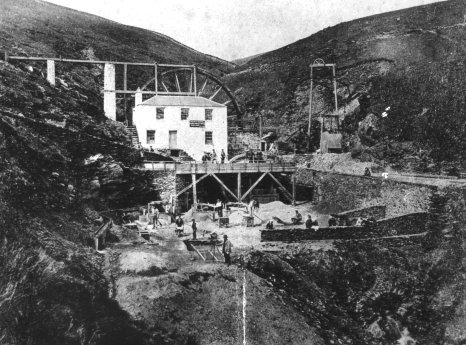

The journey of Snaefell mine throughout the ages and into the bowels of the earth, however, begins in the middle of the 19th century when a rich vein was found. The mine’s property is spread across 2.3 square kilometers of land, which was originally part of the property of the Laxey Mining Company.

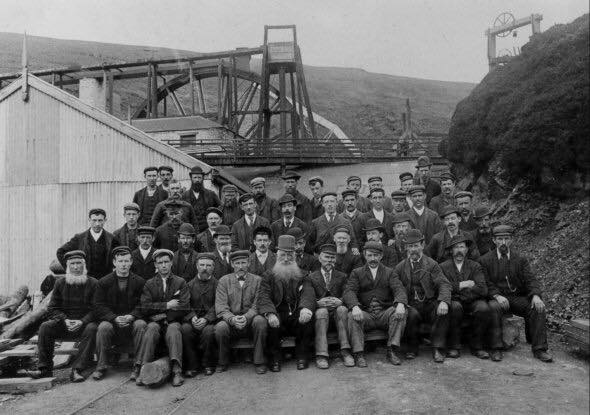

It was a prosperous place from the day it opened in 1856 and it wasn’t long before it became the center of the lead and zinc mining industry. Upon its lands there stood the house of the Captain of the mine, a couple of cottages, an office, a carpenter, a forge and even a lead store.

In its early days, the mine was run by the Great Laxey Mining Company. Later, the mine was sold to The Snaefell Mining Company, which fell into financial troubles after a short while, ultimately going bankrupt in 1870.

The fall of this company prompted the creation of the Great Snaefell Mining Company just a year later by the ex-directors of the Great Laxey Mining Company. Some years later, they too went into liquidation, which led to the second formation of the Snaefell Mining Company.

The work, in general, was done using the main shaft that followed the path and slope of the previously discovered vein. Rectangular in shape, this shaft comprised of three sections – two for the winding of the ore and one for getting in and out of the mine.

Once inside, the temperatures slowly increased and this, in turn, required the use of ventilation that was created using a series of draughts that were increased by a wooden chimney, which in turn was connected to the neighboring shafts.

But it was the ventilation itself that led to a terrible mining disaster. In 1897, the working conditions at the mine were worsening by the day. The miners were working at a depth of 312 meters where there was little ventilation could do. The temperatures at this level were unbearable, which forced the closure of the mine for the hottest months of the summer.

At these extreme temperatures, the miners used dynamite to expand the tunnels. What seemed a normal day was the start of the horrors that followed. On May 8, Saturday 1897, miners finished their last working day and left the mine.

The safety measures at the time were scanty and the miners, exhausted by the high temperatures and the lack of oxygen, forgot to extinguish one last candle on their way out. This caused a fire in the mine’s shaft that burned for hours on end, subsequently creating large quantities of carbon monoxide that completely filled the mine.

When the miners came to work on Monday, no one suspected anything and went about their usual activities and started to descend into the mine. It was not long before they realized what was going on and tried to ascend as quickly as they could, though not fast enough. Some of the miners that were near the top managed to get up to safety; others, however, were not so fortunate and remained down in the shaft surrounded by poisonous fumes.

Nineteen people lost their lives that day, the youngest of which, Walter Christian, was only 21 years old. The mine was for many in the community the only source of employment, so many of those who perished were family members, including John Oliver, 56, and his son John James Oliver, 22, both died that day, or the brothers John Kewin, 29, and William Kewin, 24; or Walter Christian, 21, and William Christian, 26. Some miners left behind children, such as John Fayle, aged 40. The mine was closed permanently in 1908 following a period of steady decline.