In its infancy, this neighborhood served as a land division place alongside a water source, nicknamed ribbon farm. Its roots go as far back as the French colonial period. The front of this farm was no longer than 120 meters, although the overall size easily exceeds 4.5 kilometers.

Years later, after its second landlord Jacques Pilet had passed away, the Barthe family purchased the land. Later, during the 18th century, an Irish businessman and fur trader John Askin acquired the property through his marriage with Marie-Archange Barthe.

Then, in the early 19th century, their daughter became the legal wife of Elijah Brush. Back then, Elijah was a lawyer, but he was on the right track to becoming the second mayor of Detroit. They got married in 1802, and Elijah bought the farm just four years later for 6,000 dollars ($114,000 inflation adjusted for 2017).

The designation given to this land is “Private Claim 1.” Over fifty years later, Elijah’s son Edmund Askin Brush had an idea. He planned to turn this old farm of his into an elite neighborhood, a place only the richest of the rich be able to enjoy.

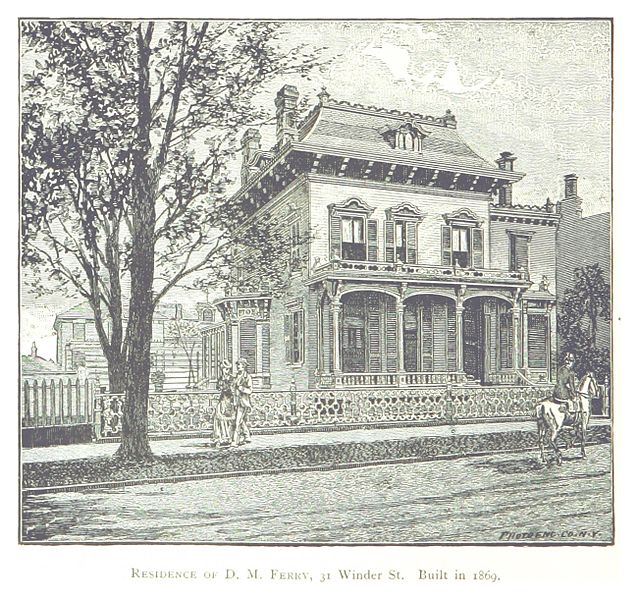

Colonel John Winder was the name given to the first street in 1852, and before long, the rest of the streets were constructed. The streets were typically named for family members of the Brush family.

All was done with great attention to detail, for the elite families for whom it was intended were well acquainted with the world of luxury. Part of the land apportioned into large and costly parcels. This part of the neighborhood was later filled with expensive mansions and religious structures.

On the other hand, the east side of the land was divided into little parcels no bigger than 15 meters, offered for a smaller amount of money but a rule required that even the plots on the east side feature big mansions.

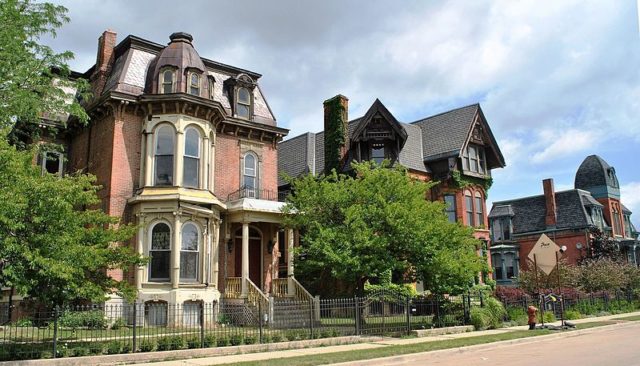

This meant that the neighborhood as a whole would receive one homogeneous look. Everything went according to plan, and soon this place received the moniker “Little Paris of the Midwest,” according to the Detroit Historical Society.

The architects behind these mammoth mansions were veterans in their trade such as George D. Mason or Albert Kahn, the most famous architect of Detroit and the man behind the Fisher Building, Ford Motor Company, Lamp Factory, Highland Park Ford Plant, and Packard Automotive Plant.

Brush Park featured many famous and influential people among its residents. Even Albert Kahn made a home in Brush Park when he decided to build his house there in 1906.

The rest of the residents were successful traders, merchants, bankers, bank presidents, and manufacturers. By the turn of the century, Brush Park was slowly changing its appearance. During this period the neighbourhood received its first apartments. This happened in 1901 and saw the beginning of a decline in opulence for the neighborhood.

The neighborhood’s decline began in earnest at the start of the 20th century as a result of the success of the automotive industry. This type of transportation meant that the wealthy could now live farther away from the noise and chaos of city life.

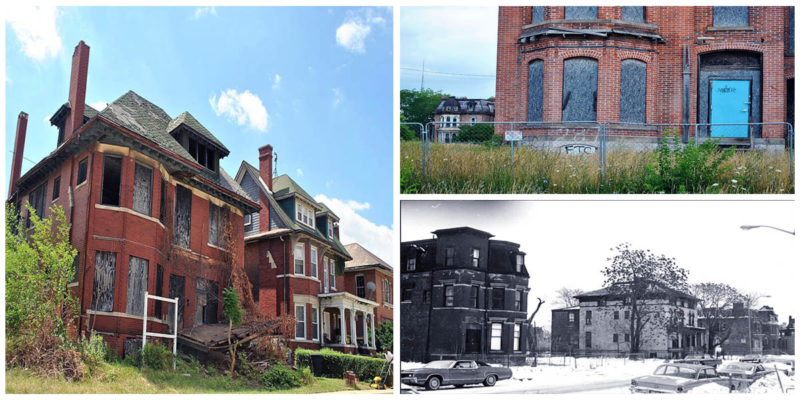

More and more mansions were being demolished and replaced with fewer luxury buildings. Slowly this place was being taken over by the working class. The final blow came during the 1970s and 80s when crime began to rise in Brush Park.

Many people felt that this is no place to call home and simply moved out. What was left was a huge number of abandoned buildings and structures left to rot away.

But all of this is about to change as the neighborhood is slowly being redeveloped and restored. Much of the historic houses are being preserved and put up for sale starting from $500,000 and up to $2.5 million.