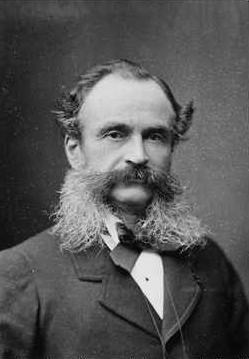

Marble Hill was the brainchild of Lieutenant-General Sir William Jervois, a British military engineer and diplomat who was appointed Governor of South Australia by Queen Victoria in 1877.

Constructed between 1878 and 1880, the former Vice-Regal Summer Residence was used by the incumbent Governor from 1880 until January 2, 1955, when the property was devastated in what became known as the Black Sunday Bushfires. Governor Robert George, along with his family and the staff, were unable to flee the grounds of the burning house, but miraculously escaped harm by hunkering under wet towels in the shelter of the driveway wall. After the fires had burned out, an unsuccessful attempt was made to demolish the Marble Hill residence. Renovation was deemed an inappropriate use of public funds and it was left abandoned.

A small portion was renovated by the National Trust of Australia in the 1970s, but it was not until 2007 that the State sold the property into private ownership, under a Heritage Agreement. Work is still ongoing, however much of Marble Hill has now been restored to it’s former glory, and the stables are transformed into a beautiful wedding and events venue.

Since it’s proclamation as a British province in 1834, each Australian state is appointed a Governor to rule as viceroy — the legal representative of the monarch, currently Queen Elizabeth II of Australia (and England). Similarly to the U.K. system, the head of the elected Parliament of South Australia is formally appointed by it’s Governor on behalf of the royal head of state.

In 1877, the existing summer residence in what is today Belair National Park had been used by several consecutive governors, but all of them found the house to be inadequate in size and not suitable for a governor. On his arrival, Governor Jervois commissioned a new house in the heart of the comparatively cool Adelaide Hills, bigger in size and comfort, and with a clear view over Adelaide harbor.

In a ploy to ensure that the landowners didn’t bump up the price when approached by Government Officials, they were sent “in disguise” as ordinary working-class folk to arrange purchase of the plot.

Jervois selected a locally well respected architect named William McMinn to design the new house, following Jervois’ own drawings. However, in a demonstration of true government bureaucracy, McMinn and the builders were overseen by another, Government appointed, architect, plus an on-site supervisor.

In accordance with the fashionable Gothic Revival movement of the era, Marble Hill House was built in Scottish Baronial style, but with modified features, like high ceilings and wide balconies, to help keep it’s occupants cool in through the scorching Australian summers. The result was a curious architectural mix of gargoyles to ward off evil spirits and a veranda running around three sides to shield the house from the relentless sun.

Originally designed to have 40 rooms, only 26 were built. It was left so that the house to be further extended on one side — there were even fireplaces built into the outside walls. Despite the paring down in size, Marble Hill House ran so far over budget that in December 1879 George Charles Hawker, at that time Commissioner of Public Works, invited the Parliamentarians to witness the new and bigger house. Seeing the exquisiteness and splendor of the new residence, they were convinced that Jervois made a good investment.

The first problem encountered by the builders was to create an access road through rough and notoriously steep terrain. From removing up to 15 feet deep of bedrock to level the site, to hauling the sandstone blocks up from the quarry at Basket Range, everything had to be done by hand and horse-cart. In one story of how the property was given it’s name, Jervois was wrongly informed that marble had been found during the groundworks. In fact, it was the less-valuable rock quartzite, but the name Marble Hill stuck. The entrance hall was laid with a white marble floor, possibly more to help keep the place cool than to match the house’s name.

The caretaker’s cottage and the stables were erected on the west side of the property. There were a number of formal gardens that were popular with most of the resident Governors, being used for everything from picnic lunches and cricket matches.

A total of fifteen Governors used this house as a summer escape in the cooler hills overlooking Adelaide city. The first one, of course, was William Jervois, spending three seasons here from 1880 to 1883, and the last was Sir Robert George who was Governor from 1952 to 1955.

Of course, summer bushfires are common in the Adelaide Hills. Marble Hill was chosen because the site was not in a high-risk zone, but still the house had several close encounters. Each time, residents and firefighters managed to defend the main house, but nothing could be done on Black Sunday: January 2, 1955. Strong winds pushed the fire towards the house. With scorching temperatures, the fire got close enough that the seaweed used as insulation in the lead roof caught alight — so fierce was the heat that molten lead from the roof dropped down and covered the cars. Faced with a wall of fire, the occupants were trapped on the hilltop until the inferno passed over them. Luckily everyone survived, even the kitchen cat.

Marble Hill was gutted. With costs for revamping too great, the house was left in ruins. Over the years the house was used as a bushfire lookout and a tourist attraction.

In 2009, Mr Edwin Michell and his wife Dr Patricia Bishop bought the property and are now working on its renovation in accordance with the Heritage Agreement. The revamped stables and New Barn are complete, and are now available for hire as a stunning wedding venue. A neighboring vineyard that has also been added to the estate now produces Marble Hill branded wine. There is a series of open days throughout the year, which the owners use to “highlight the history and heritage of the Vice-Regal property.”