When it comes to human suffering, nothing compares to the concentration camps of the Second World War, responsible for destroying millions of lives. From Auschwitz to Treblinka, the enterprising Nazi teams made sure that these “death camps” lived up to their promises.

About 6 million Jews were killed in the Holocaust, and that’s just Jews only.

Estimates range from a total of 12 million to 20 million people who died as an answer to Hitler’s “Final Solution,” in camps, ghettos, or taken from their homes and shot. The list includes Romani, Slavs, Jehovah’s Witnesses, people with disabilities, political opponents (including priests), homosexuals, prisoners of war, and more — all were deemed undesirable.

The story begins with a politician who on his way to power promised a better tomorrow for his fellow citizens. But at what cost?

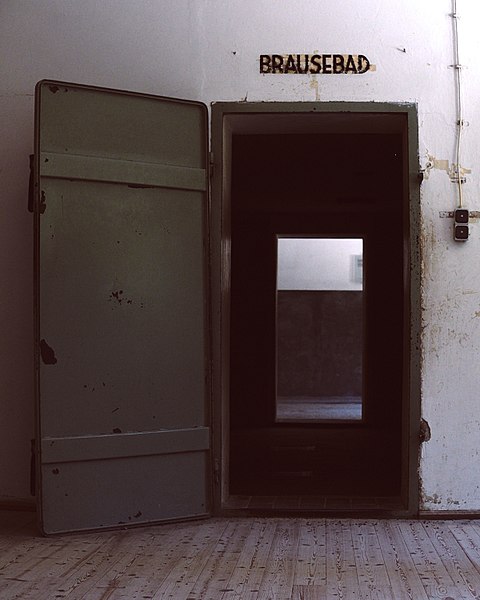

Hitler was installed as Chancellor of Germany in January 1933, and established dictatorial control over the country with the signing of the Enabling Act on March 22, 1933. On this same day, Dachau camp opened its doors — announced to the press by Himmler as “the first concentration camp for political prisoners.”

It was located on the borders of Dachau, a town in southern Germany to the north of Munich, on the grounds of an abandoned munitions factory.

Being the first of its kind, Dachau concentration camp served as an example for all future camps. In its first year, the camp processed close to 4,800 people. At first the inmates consisted of German Communists, trade union members, and other political prisoners.

When the Reich Citizenship Law was passed on September 15, 1935, as part of the Nuremberg Principles, it removed citizenship rights from these deemed not of German or related blood.

Prosecutions under the new laws, designed according to Hitler’s ideals to preserve a “pure” Aryan race, did not take place until after the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. However a variety social changes beginning in April 1933 made life very uncomfortable for those now marked as “other.”

The population of Dachau diversified as homosexuals, gypsies, and black people were brought in, as were repeat criminal offenders, resistance fighters, and other “asocials.”

The Jewish population at Dachau was relatively low up until 1937. That is when the Third Reich gave out the order for the munitions factory to be demolished so that room could be made for a new set of buildings.

Naturally, the prisoners were forced to do all the labor, from demolition to construction. The work was finished one year later and large numbers of Jewish people were brought to Dachau; the law at that time was such that the Jews were given a get-out-of-jail-free card if they were willing, and able, to leave Germany. A chance that would disappear very soon.

Life inside Dachau camp was torturous. Brutal treatment and punishment were an everyday event; for instance, people were locked in so-called standing cells or were tortured using the strappado — a torture contraption where a person is hanged from a pole or a tree by his wrists, generally resulting in dislocated shoulders.

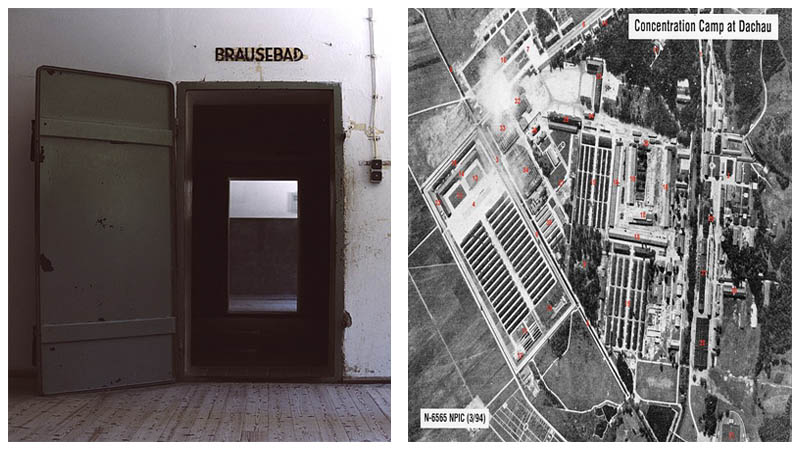

A gas chamber was installed in 1942 as part of a new crematorium building, Barrack X. As in other camps, it was disguised as a disinfection block, or brausebad, with fake shower heads so that the victims would go in willingly. The only difference though between this camp and many others is that the Dachau chamber was never used.

But Dachau had its own dark secrets.

It was here that Nazi scientists performed inhumane experiments upon the inmates. Experiments such as purposefully causing frostbite to study the effects of it, or forcing people to only drink sea water. Experimenting with drugs that caused hallucinations was also on the list of torture tactics.

The prisoners were held in 32 barracks, one of which was reserved for medical experiments. Executions took place in the central courtyard, although a huge number of deaths in Dachau and its sub-camps were due to starvation and disease.

The camp operated during the whole reign of the Third Reich. It was liberated by U.S. troops on April 29, 1945, and by October of that year was being used to hold war criminals and members of the SS ahead of the Dachau Trials, as well as deserters from the Russian army. A part of Dachau formerly used by prison guards became a U.S. military base, the Eastman Barracks, until 1960. It is today used by the Bavarian rapid response police unit.

Dachau Camp processed nothing short of 160,000 people and tens of thousands died as a result of the treatment they received in there.

Nowadays, this camp serves as a memorial site and stands open to all those who wish to pay their respects to the people who suffered here, and throughout the Second World War in general.