It is quite a surprise to stumble upon a sign that reads “Lake Valley” with no lake to be seen anywhere near, nor a pleasant valley to walk through. The sign has a different mission.

It is here to tell a story of a once prosperous town, a tale that begins with two miners, George W. Lufkin and Chris Watson. Lufkin and Watson were the first to scour these hot desert sands in Sierra County, New Mexico, and the first to feast their eyes on the lovely silver ore found there. The year was 1878, and silver was found in abundance.

Like all good news, this one too started to run freely. Word of their discovery quickly left the scorching heat of Lake Valley and reached the ears of ever-hungry prospectors, who travelled to the site to stake a claim for themselves — a silver rush was born.

Soon the once lonely desert valley was no longer filled with solitude. The area also attracted the attention of businessmen George D. Roberts and J. Whitaker Wright. They employed mining engineer George Daly to evaluate the situation.

Pleased with what he found, Daly bought Lufkin and Watson’s claims in 1881 on behalf of his employers, and the site was split into five mining companies: the Sierra Apache Co., Sierra Bella Co., Sierra Grande Co., Sierra Madre Co., and the Sierra Plata Co.

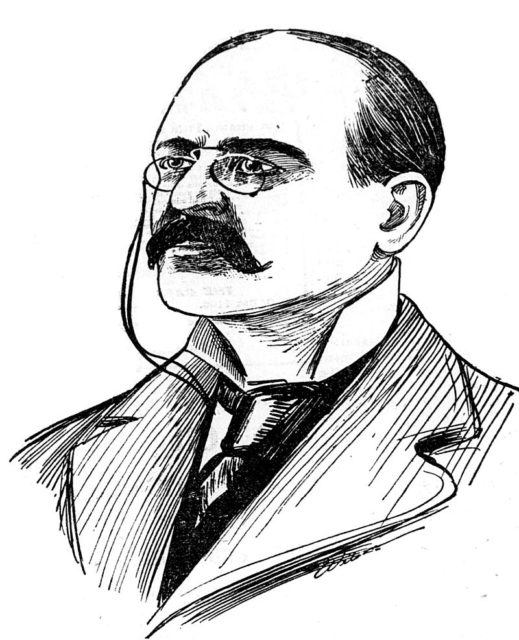

Unfortunately for investors who bought shares in the Lake Valley mining companies, Wright turned out to be an unscrupulous confidence trickster.

Even though Lake Valley had some very successful years, there was no return to be made for the shareholders. In fact most lost money — apart from the wily Wright.

And there were plenty of people who thought putting their cash into Lake Valley was a good bet. Word had got around that the Sierra mining companies were paying close to $100,000 in dividends each month.

In reality the figures had been hugely exaggerated by Whitaker Wright, who went on a wild speculation run and thus drove share prices up.

After filling his pockets on the profits from selling his own shares, Wright returned home to London, England, where he continued his dishonest career. He would cause a scandal some years later, in January 1904, when he committed suicide by taking cyanide inside a London courtroom after finally being convicted on charges of fraud.

The big breakthrough for Lake Valley came in 1881. Blacksmith-turned-prospector John Leavitt had taken lease of a claim from the Sierra Grande Company, and it was he who first encountered a chamber that could be compared to Aladdin’s Cave. The Bridal Chamber Mine would go down in history as one of the richest silver deposits ever discovered.

Within the Bridal Chamber was a four-feet-thick lode of horn silver of the highest quality. One chunk, displayed at the 1882 World Exposition in Denver, was valued at $7,000. In total, 2.5 million troy ounces of silver came out of Bridal Chamber Mine.

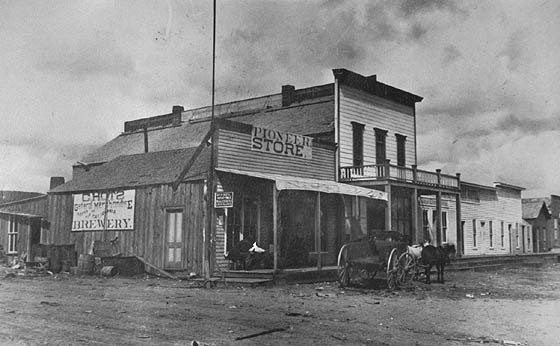

By 1884, the town was packed with people and saloons. Gunfighters too were part of Lake Valley’s everyday events. The most illustrious of them all by far, “Longhair Jim” Courtright, became Town Marshal in 1882.

In 1884, the Santa Fe Railroad came to town and the future of Lake Valley was secure. Or so they thought. But before the end of that year, the Bridal Chamber was exhausted and the boomtown bubble began to deflate.

Some parts of the mines kept operating, their focus turned towards the next big breakthrough. The silver ore started to drop in quality and with profits on a speedy decline, the smelters had no choice but to shut down.

Almost crushed by the 1893 silver panic, when prices crashed to a record low, the final blow to the future of Lake Valley came in 1895, when a fire destroyed many of the buildings on Main Street.

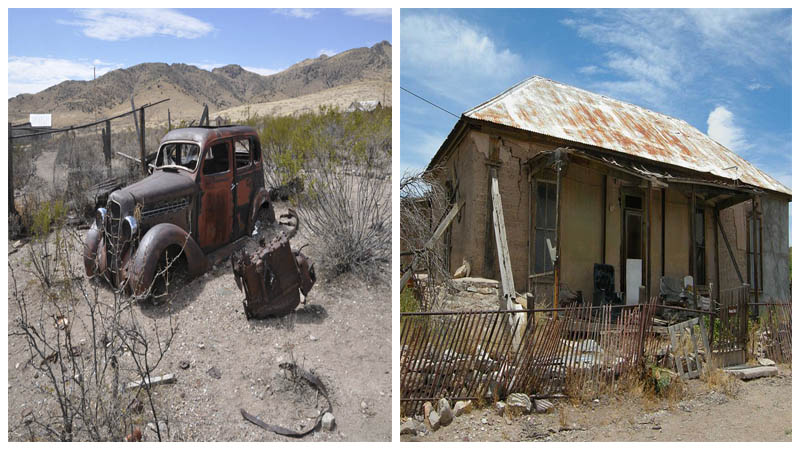

By the start of the 20th century, the population was reduced to just 200 people. The town’s decline was interrupted by the need for manganese during the two World Wars, but in 1954 the post office was closed and the few remaining residents drifted away. Pedro and Sabina Martinez were the last residents to leave Lake Valley, in 1994.

Today Lake Valley town is under the care of the Bureau of Land Management, however land still owned by mining companies is closed off and probably unsafe due to the old mine workings.

There is a small museum and tours can be arranged with the on-site caretaker during the Historic Townsite opening hours.