The glass company named Fostoria was first registered in July 1887 in West Virginia.

Just before this, natural gas had been discovered in Fostoria, Ohio and was offered at a very low price to encourage businesses to set up there. Glass companies preferred to use gas as fuel because it left no residue, it had a uniform heat, and was easier to control than other fuels.

Production at the factory began on December 15, 1887, with 125 workers. However, the natural gas supply in those parts turned out to be short-lived, as other companies were interested in this location and the combined usage exhausted the resource.

Consequently, the factory was forced to relocate to Moundsville, West Virginia, in 1891. At that time, Moundsville had an abundance of natural gas and coal. Moving to a new place was not so simple. The owners decided to relocate in April 1891 but didn’t manage to make the move until the end of the year.

This was because a restraining order was requested by the Crimmel family, who were not only workers in the factory but also shareholders. The Crimmels filed a lawsuit because the owners of the company did not consult with the shareholders about the move.

Ultimately, the Crimmels lost the case and the restraining order was canceled. Fostoria was able to move at the end of December 1891.

As an incentive to set up their business there, the company had been offered coal at a low price for the next ten years as well as $10,000 finance from the local community. About 60 workers moved from Ohio to the new plant in Moundsville, West Virginia.

In 1903, a three-story brick building was built on the site in addition to the two furnaces already there. This new furnace had a capacity of 14 pots. The number of employees by this time was about 800 people.

Until 1916, the company was engaged in the production of mainly oil lamps, glasses, and toggle switches for restaurants and bars. However, Prohibition meant that they switched the focus of their output to tableware.

The first products the company made were pressed tableware such as butter and sugar bowls, bar supplies, and lamps. Candelabras became a specialty, and the company also produced inkstands and paperweights.

In 1924, the company produced a set of tableware which was made entirely of crystal. The next year, it made colored dinnerware. These unique products were the subject of a national advertising program in 1926.

By 1926, the company could boast a catalog of 10,000 different products. In 1928, the company acquired the status of the largest producer of handmade glass products in the country.

An interesting fact is that every US president from Eisenhower to Regan ordered some kind of glassware from Fostoria Glass because the company also produced glass with the government seal and other custom designs.

1950 was a peak year for the plant. The number of employees exceeded 1,000 people, and more than eight million crystal and glass products were produced that year.

During the following decade, the president of the company is quoted as saying that they faced competition from other domestic companies as well as imports and automation. In the 1970s, foreign competition also appeared as the import of machine-made lead dishes had grown significantly.

These factors, combined with changing customer preferences, all significantly affected the company’s profitability. The company tried to automate the production process, which ultimately led to the loss of labor. At one point, the company even faced strikes.

Lancaster Colony Corporation, based in Columbus, Ohio, acquired the Fostoria factory in 1983. The final closure of the plant took place on February 18, 1986, since Lancaster Colony considered that all the facilities were already outdated and foreign competition had grown significantly.

Many of the molds were sold off which meant that other companies continued making Fostoria products after the company closed. In fact, some molds and Fostoria workers went to the newly merged glassware company of Dalzell-Viking, so that there was very little difference between original Fostoria products and those made by the new company.

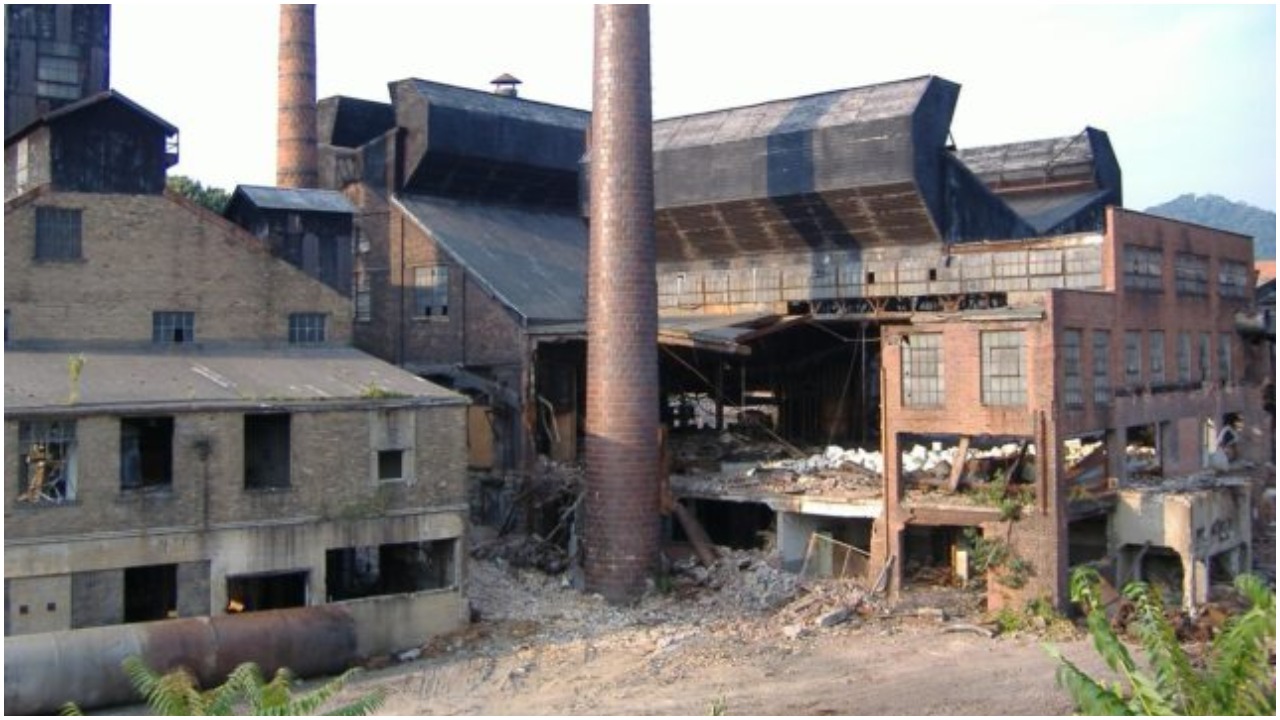

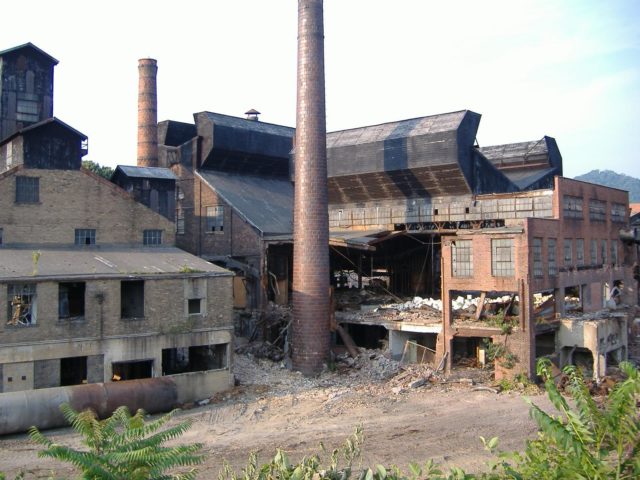

Various parts of the building gradually fell into disrepair due to the lack of necessary maintenance. Strangely enough, urban explorers report how conveyors and kilns remained without much vandalization. Eventually, the abandoned complex was completely demolished in 2006 after 99 years of excellent work and 20 years of desolation.

Fostoria Glass Society of America Inc. bought some property in Moundsville next to the county courthouse and founded the Fostoria Glass Museum there. The museum is open from Wednesday to Saturday from 13:00 to 16:00 during the months of March-November. More information can be found on the museum’s official website.

The photographs were taken during a pause in the demolition of the plant in 2006. They were posted with permission from their owner – Willy Nelson. He lives in Moundsville, WV, and owns several social media accounts which you can find on his Flickr account where he shares his different types of photographs. More photos of the plant’s demolition are available in his Flickr album.

St Agnes Church in Detroit, Michigan