It is one thing to name a ship after a great captain or a region, but it is a completely different scenario to name it after the very personification of darkness in Greek mythology: Erebus.

Roughly translated, this word means “deep darkness” or “shadow.” According to the Greek myths, Erebus was one of the primordial deities — the group of gods that came before everything else.

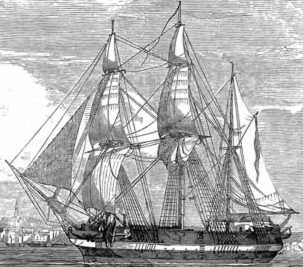

Getting out of mythology and into more recent times, the name Erebus was given to a mighty ship, a Hecla-class bomb vessel of the British Royal Navy whose only job was to bring upon its enemies the very thing its name represented.

Sir Henry Peake designed the ship, and construction took place at Pembroke dockyard. Once finished, the ship measured 105 feet (32 meters) in length and had a tonnage of 372. It had two mortars and no less than ten guns. On June 7, 1826, it was launched for the first time.

HMS Erebus served in the Mediterranean until 1836, when it was selected as the perfect vessel to participate in the Ross Expedition to the Antarctic alongside HMS Terror. Having James Clark Ross as captain meant that the expedition was seen as a guaranteed success.

The journey started from Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), with Antarctica as the final destination.

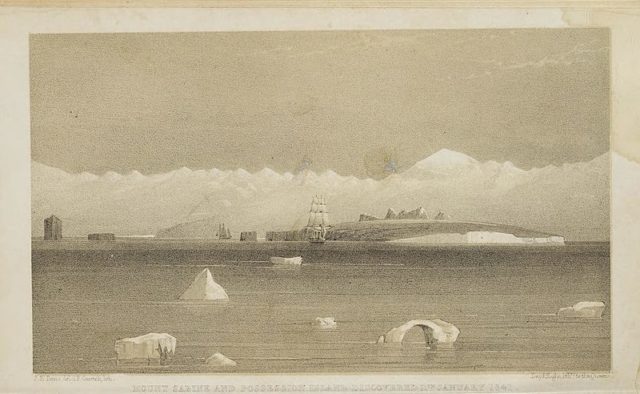

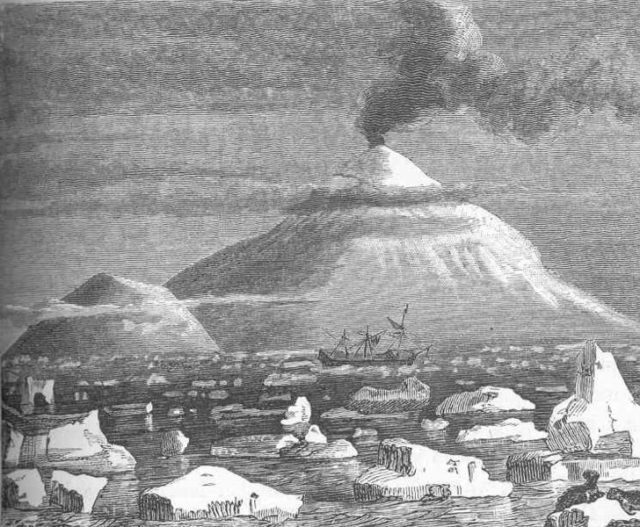

Mile after mile, the expedition discovered new lands, regions, and mountains and named them after politicians and scientists. The volcanoes Mount Erebus and Mount Terror on Ross Island were also named on this voyage.

The expedition ended successfully in 1843, and the crew returned with many discoveries such as new plants and birds as well as oceanographic data.

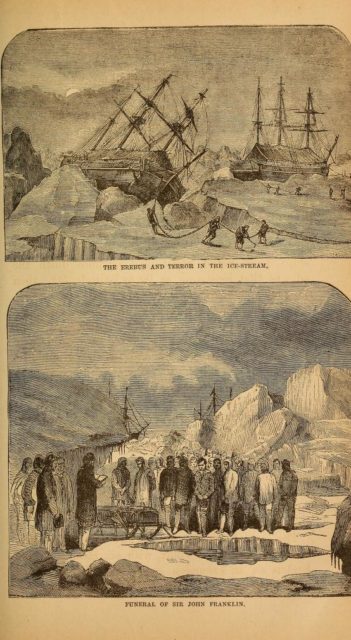

However, many things still remained tantalizingly unknown. Another expedition was organized just two years later in 1845. HMS Erebus and HMS Terror were once again the two vessels of choice.

Being no stranger to these waters, HMS Erebus set forth on the journey to explore the Canadian Arctic, but this time, the ship received an upgrade: a 25-horsepower locomotive steam engine.

The expedition was led by Sir John Franklin. Having one voyage behind them, no one suspected that this one might fail, let alone that it would be the last voyage for every crew member on board.

The idea behind the trip was to gather more data about the Arctic as well as to complete a crossing of the Northwest Passage. Further details of the trip, however, begin to get hazy.

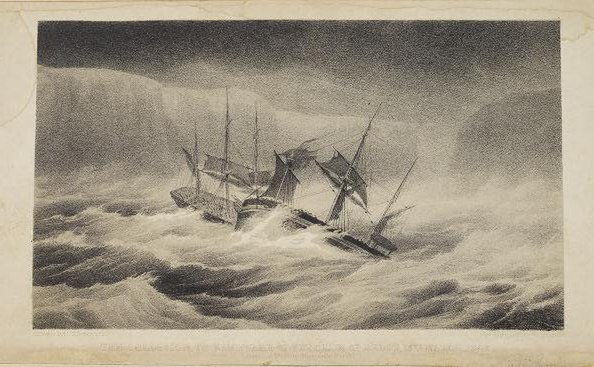

The last known thing about the two ships is that they entered Baffin Bay in August 1845. From that point on, they were lost in time.

Many searched for them, and what was subsequently discovered was that the ships had become icebound. As such, the only logical approach was to abandon them.

The crew members did so and left the ships alone, bracketed by ice. The Arctic is known to be unforgiving, however, and the 130 people were about to experience this first hand.

In time, all of the crew members died from various causes such as hunger, hypothermia, and scurvy. Their bodies remained undiscovered for decades until newer expeditions managed to find them. As for the fate of Erebus, she remained a ghost until 2014.

In 2014, a search team led by Ryan Harris and Marc-André Bernier set forth on an expedition of their own with one goal in mind: to find the two lost ships from the Franklin expedition. On September 2nd that same year, a wreck was found.

One month later, it was discovered that the remains belonged to HMS Erebus. With this, all the rumors of it being kidnapped by extraterrestrials, stories of cannibalism, and speculations of it having been teleported to an alternative universe were laid to rest.

Another Article From Us: SS Valencia and the Graveyard of the Pacific

To this very day, HMS Erebus remains deep in the waters of the Arctic surrounded by the very darkness that its namesake once created.