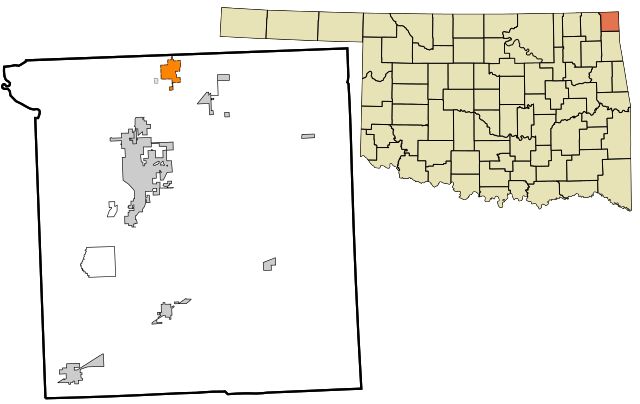

The ghost town of Picher is located in Ottawa County, Oklahoma, United States of America. The town was founded in the days when the United States entered into World War I. Picher, situated at the middle of the Tri-State Mining District, an area covering more than 2500 square miles in southwestern Missouri, southeastern Kansas and northeastern Oklahoma, became a leading national center of the lead and zinc mining industry.

In September 2009, the year after the town was struck by an EF4 rated tornado, the residents of Pitcher left the town. But the tornado wasn’t the main reason why this once thriving community became completely deserted, although it took eight lives and damaged 150 houses. The real problem was, and still is, the lead and other heavy metals in the drinking water and the soil. The Environmental Protection Agency of USA categorized the small town of Picher as the most toxic town in America.

The birth of Picher was in 1913, during the growth of the Tri-State mining district, when Harry Crawfish staked a claim to the lead and zinc ore at this location. A flourishing community started to grow literally overnight around the new mines and soon developed into a new town, which was incorporated as a municipality in March 1918. It was named Picher after O. S. Picher, the owner of Picher Lead Company.

The wartime demand for metal production was answered by the Tri-State district. During World War I more than fifty percent of the zinc and metal used in the war was produced by the Picher district, and during both World Wars combined, 75 percent of all the bullets and bombshells used by American soldiers were produced from metals mined in the region. Before the discovering of zinc in the area around Picher, Germany had monopoly of the zinc industry, because they controlled the zinc mines in Belgium.

The population of Picher kept on growing, from 9000 inhabitants in 1920 to approximately 14,ooo at it’s peak population in 1926. The mines employed 14,000 miners plus another 4000 people working in mining services. Many workers came to work in Picher from the near towns, but also from as far away towns as Joplin, Missouri and Carthage. Production fell throughout the 1930s as the Great Depression swept the country meaning that many employees were laid off and people started to leave the town, but World War II brought Picher another boom.

By 1967 the mining came to an end and so water pumping from the mines ended. The contaminated water left behind in approximately 14000 abandoned mine shafts, 70 millions of mine crushed rocks and 36 million tons of mill sand and mud became a huge environmental problem. Many man-made mountains of mining waste, known as chat piles, formed of crushed limestone, dolomite and silica-laden sedimentary rock and about 300 feet high had accumulated after the years of extracting the metal ore.

The town in the 1970s had nearly 2000 inhabitants and the chat piles became an essential part of the town’s culture. People would go onto the chat piles for picnic and kids were biking on them. But, at the end of the 1970’s they started to realize that their health was in danger. Pollution from heavy metals from the chat piles became apparent. Waters began running red and people started to get sick very often. The town slowly became hazardous.

It was also discovered that because of years of unregulated mining operations, numerous large tunnels had been carved under the town. Sinkholes started to appear as mines were abandoned leaving many of the town’s structures unstable. Officials realized that the safety of the inhabitants couldn’t be guaranteed. They determined that 86 percent of town’s structures were dangerously eroded and the town was at risk of collapse at any time.

In June 2009 the authorities started the permanent relocation of the inhabitants from Picher. But some people refused to leave the town and in November 2010 it was reported that six residences remained occupied and one business was open. The last inhabitant to leave, Gary Linderman, owner of the Ole Miner Pharmacy, died in 2015.

Picher officially became a ghost town when last inhabitant to leave, Gary Linderman, finally abandoned his Ole Miner Pharmacy. This hero had vowed to remain in the town so long as anybody might need him there.

Most of the commercial structures were demoloshed starting from 2011. Today the few still left buildings are badly decayed. The government plans to return the land to the Quapaw Nation who have already bugun to restore the area. The former inhabitants of Picher think that a restored prairie is a better solution than empty and collapsed buildings.