The abandoned Eagle Mountain Railroad is a blast from a great past, when “iron roads” ruled, forging their way across the United States. Its location is incredibly alluring, while at the same time quite sad. For three decades, these railroad tracks were left rusty, unused and covered in weeds. Today, all that remains is a vacant trackbed.

Why was the Eagle Mountain Railroad built?

Erected in 1947-48 to haul iron ore from the Eagle Mountain Mine in the California desert to what was then the Southern Pacific Transcontinental Mainline. At 51 miles in length, it was one of the longest rail construction projects of the 20th century, crossing several washes via wooden bridges and cast-iron culverts, the longest being a 500-foot-long steel bridge at Salt Creek Wash.

The Eagle Mountain Railroad ran east from a connection with the Southern Pacific Transportation Company in Coachella Valley, known as Ferrum (Latin for “iron”) to the Eagle Mountain Mine, which excavated iron ore from the area. It was then transported directly to Henry Kaiser’s steel mill in Fontana, the only integrated steel plant on the West Coast of the United States.

As with similar mining operations, a town was established nearby to house miners and their families. At its peak, 4,000 people lived in Eagle Mountain in 400 homes, boarding houses, trailer spaces and dormitories. In terms of amenities, the mining town also had churches and schools, a bowling alley, a community swimming pool and an auditorium, among other structures.

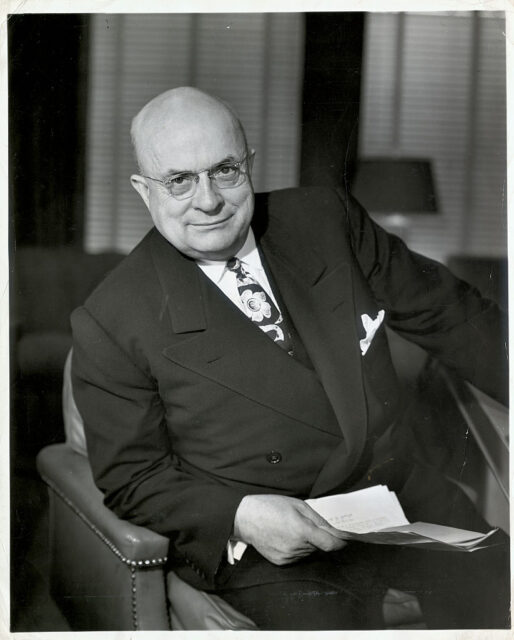

Henry Kaiser was a famed industrialist

A great American industrialist, Henry Kaiser founded more than 100 companies, including Kaiser Aluminum, Kaiser Steel, and Kaiser Cement and Gypsum. Taking the profits from his initial project, he went on to build everything from dams and houses to ships.

Kaiser’s hallmark was that he didn’t rely on external suppliers for raw materials. For example, he erected a cement plant and a nine-mile-long conveyor belt to transport material when he began work on the Shasta Dam in northern California. To build his ships during World War II, he constructed a steel mill and purchased mines and railroads to feed it.

His legacy has endured long after his death. In his honor, a class of US Navy fleet replenishment oilers was named for Kaiser, and he was posthumously inducted into the California and Labor Hall of Fames.

Operating across the California desert

At its peak in the 1950s-70s, two 100-car ore trains departed from the Eagle Mountain Mine each day. The drivers handed over their full trucks at Ferrum and returned to the mine. By the late 1970s, this was down to one train a day, and just three to five operated per week by the early ’80s.

During the height of its operations, the Eagle Mountain Railroad also played host to several films, including The Professionals (1966), starring Lee Marvin, Burt Lancaster and Robert Ryan, and Tough Guys (1986), also starring Burt Lancaster, as well as Dana Carvey and Kirk Douglas.

The Eagle Mountain Mine closed down in 1984. However, the railroad continued to be used to haul stockpiled ore that was mostly shipped overseas. The last commercial train was reportedly on March 24, 1986. However, rail speeder club members have alleged they were using the railroad in 2011.

The Eagle Mountain Railroad was left abandoned

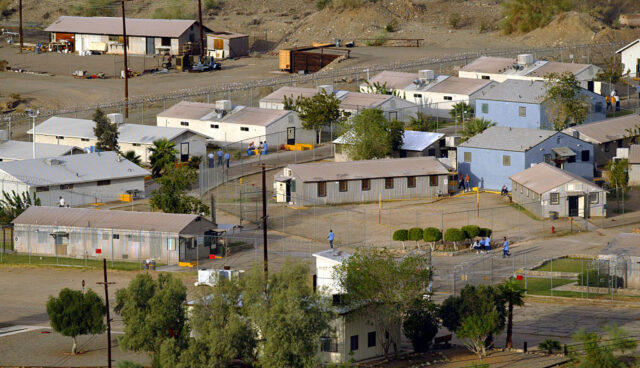

Following their abandonment, the Eagle Mountain Mine and Railroad became the center of many discussions regarding their repurposing. The California Department of Corrections thought the sites would be ideal for establishing a privately operated prison for low-risk inmates, while a second proposal envisioned the mine as a landfill.

With no regular maintenance of the tracks or culverts since the mid-1990s, the Eagle Mountain Railroad was left at the mercy of the harsh desert climate and monsoon floods. The worst damage resulted in the washout of the trackbed.

What remains of Ferrum and Eagle Mountain?

Very little still exists of the Ferrum switching yard, where the Eagle Mountain Railroad once connected with the Southern Pacific Transcontinental Mainline. All that remains at the site is a maintenance-of-way structure and part of the wye, with the rest having been removed.

More from us: Do Spirits Lurk the Halls of the Abandoned Yorktown Memorial Hospital?

As for the Eagle Mountain Railroad, work began in April 2017 to rip the tracks up between Ferrum and the Eagle Mountain Mine. Work was anticipated to be completed by 2023. The same can’t be said for the nearby town. While it has been abandoned, it’s now one of the best-preserved ghost towns on the West Coast.