Hashima Island – also known as Gunkanjima and Battleship Island – is an abandoned swath of land off the coast of Nagasaki, Japan. One of the 505 uninhabited islands within the Nagasaki Prefecture, it’s an example of the rapid industrialization the country underwent during the 19th and 20th centuries. It’s also a dark reminder of Japan’s colonial past and the slave labor that came from it.

Discovery of coal on Hashima Island

Coal was discovered on Hashima Island in 1810, and from 1887 until 1974, it was continuously used as a seabed coal mining facility. The island was purchased by Mitsubishi Goshi Kaisha in 1890, and while under its control excavated an estimated 15.7 million tons of coal.

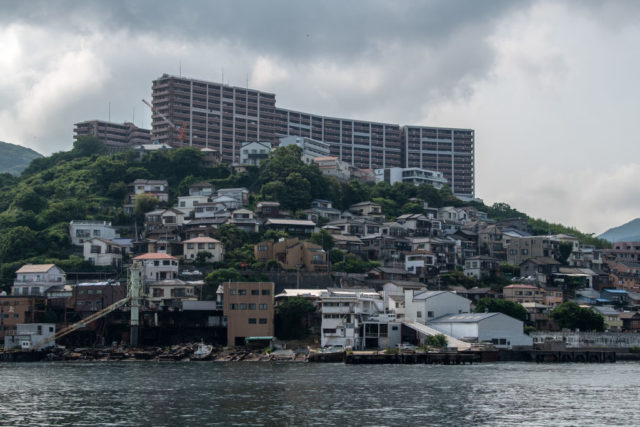

To ensure Hashima remained secure in the face of harsh weather conditions, Mitsubishi constructed seawalls. In 1916, with the company having moved thousands of employees to the island, the first of many reinforced concrete apartment buildings was also built. Concrete was used to protect against the destruction caused by typhoons.

Over the next 55 years, more concrete buildings were constructed, including a school, town hall, hospital, community center, swimming pool, cinema, clubhouse, communal bath and pachinko parlor. Rooftop gardens and shops were also set up, ensuring the miners and their families were privy to the same amenities as those on the mainland.

By 1959, the island reached its peak population of 5,259 people. However, this began to decline in the 1960s, following the introduction of petroleum in lieu of coal. This caused much of Japan‘s mines to shut down, including those on Hashima. Mitsubishi officially shut down operations on the island in January 1974, and by that April it was completely cleared of inhabitants.

Hashima Island and the use of slave labor

While the majority of people tend to focus on the success of Hashima’s coal mines, there’s also a dark side to its history. Beginning in the 1930s and lasting until the end of the Second World War, the mines were largely run by conscripted workers from China and Korea, both of which had been colonized by Japan.

Those forced to work in the mines reported poor conditions, going as far as to call them inhumane. The humid weather meant working in the mines was often an uncomfortable experience, especially when compounded with the scarcity of food, and they were frequently faced with malnutrition and exhaustion. If they slacked on the job, they risked being beaten.

While official records state that just under 140 conscripted laborers died during this time period, other estimates suggest the number may be well over 1,000.

In 2009, Japan requested that Hashima Island and 22 other industrial sites be named UNESCO World Heritage Sites. This proposal received backlash from both South and North Korea, as well as China. South Korea, in particular, claimed the recognition would “violate the dignity of the survivors of forced labor, as well as the spirit and principles of the UNESCO Convention.”

A week before the 39th annual UNESCO World Heritage Committee meeting, Japan and South Korea agreed on a compromise: Japan would include the use of forced labor when explaining each site’s history and both countries would cooperate toward the approval of their World Heritage Site nominations. Hashima Island was subsequently approved as part of the Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining.

In June 2018, the UNESCO World Heritage Committee concluded that Japan had failed to implement measures to ensure the topic of forced labor was discussed in regard to Hashima and its other industrial sites. Japanese officials had repeatedly declined to use the term or refer to the conscripted Korean workers as “slaves.”

The committee requested Japan keep its promise to South Korea and UNESCO.

Organized tours on Hashima Island

Mitsubishi owned Hashima Island until 2002, when it voluntarily transferred it to Takashima. It then became part of Nagasaki, when it and Takashima merged in 2005. At the time, the city planned to restore the island enough to turn it into a tourist destination. While delays hampered the progress, it was officially opened to travel in April 2009.

More from us: Nagoya Castle: a gorgeous Japanese castle that fell victim to the horrors of WW2

Since Hashima was not maintained following the closure of its coal mines, several buildings collapsed, largely due to typhoon damage. There was also the danger of other buildings collapsing, but these have since been restored with concrete. For those interested in visiting the island, this can be arranged through joining an organized tour.